It’s common to hear demands nowadays for something called “decolonisation”. Apparently colonisation was the worst thing that ever happened to the peoples of the New World, and justice cannot be served until it is reversed. The media, educational and political machinery of the West is fully behind pushing the term and its logic. But what is it?

Some definitions of decolonisation refer to the colonised nation becoming independent of the colonising power. But this cannot be the sense in which most people use the term, because New Zealand has been independent from Britain for decades already and there are still calls for decolonisation. So the term must mean something else.

In most discourse, ‘decolonisation’ is a synonym for white erasure. This means the systematic removal of all white people and all white culture. It means the destruction of all white institutions – whites must not be allowed to organise in any sense. It means the criminalisation of all pro-white speech, even if spoken in self-defence (see the ‘It’s Okay To Be White‘ saga for proof). It means the demonisation of whites in speech and media (as per Marama Davidson).

Understanding this, it’s possible to look back on historical examples of decolonisation to get some clues about how it works in practice.

The first major example is Haiti. The island contained the first European settlement in the Americas, founded by Christopher Columbus in 1492. The French built it into a sugarcane colony, creating immense wealth from the product of slave labour. At one point, there were some 30,000 French living there and 700,000 African slaves.

Decolonisation came in the form of the Haitian Revolution, beginning in 1791 and ending in 1804. This sentence, from Wikipedia, says it all: “On 1 January 1804, Dessalines, the new leader under the dictatorial 1805 constitution, declared Haiti a free republic in the name of the Haitian people, which was followed by the massacre of the remaining whites.”

A second major example comes from Algeria. A French colony since 1830, Algeria was considered an integral part of France for over a century. Algerian French culture was established enough that it managed to produce a mind as great as that of Albert Camus. After Algeria became independent in 1962, some 800,000 French colonials were driven to France.

The next major example is Rhodesia. The white population of Rhodesia peaked at around 300,000 in the mid-1970s. After the Rhodesian Bush War and the reformation of Rhodesia as Zimbabwe in 1980, wholesale ethnic cleansing began. Between 1980 and 1990, some two-thirds of the white population were driven overseas.

Rhodesia is, along with Haiti and Algeria, an archetypal decolonisation story, in the sense that it ended with the extermination of white settlers. Anyone who thinks that decolonisation is about equity is either dishonest or stupid. The spectre of decolonisation should, if we are thinking clearly, invoke images of mass slaughter and rape.

South Africa is the best major example of ongoing decolonisation today. Since 1993, the year of the referendum that introduced black rule, the white proportion of the population has halved, from 16% to 7.5%. Almost one million white South Africans have been driven overseas, an ethnic cleansing that surpasses Algeria in absolute numbers, if not proportion.

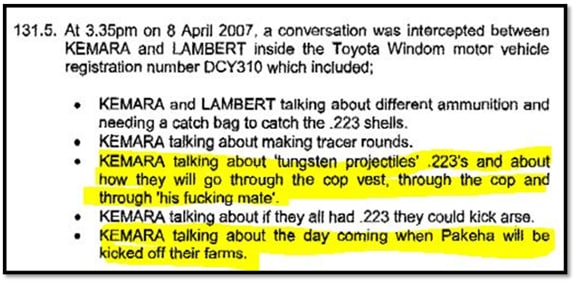

Decolonisation in New Zealand would likely involve a path similar to the places above. There is a sizable number of radicals, aided by the usual communists and fellow travellers, who dream of doing to white New Zealanders what was done to white people in Haiti, Kenya, Algeria, Rhodesia, South Africa and other places. Some of them are influential.

It might be argued that Maoris simply don’t have the numbers to repeat the wholesale ethnic cleansing of Haiti, Algeria or Rhodesia. That may be true, but the main principle of decolonisation is the progressive exclusion of all white people from all positions of power or influence, however long it takes. This can be enacted without needing to win any military victory.

For example, some co-governance arrangements involve a 50:50 powershare between Maori interests and non-Maori interests. This is naturally a form of white erasure because it reduces the proportion of power held by whites, from the 70% befitting their population, to less than 50%.

From there, it’s possible to disenfranchise white people further by awarding scholarships preferentially to non-whites, by reserving spaces in prestigious educational courses specifically for non-whites, requiring some proportion of Government procurement to be made with non-white businesses, funding and promoting non-white arts and media, and dozens of other tactics.

It’s easy to imagine that, after a few decades of this, the situation for New Zealand’s whites would start to look like the situation of South African whites today.

The reason why co-governance is so controversial is that New Zealand’s white majority, consciously or not, can sense that the push for it is motivated by the same sentiments that led to the extermination of white populations elsewhere. As such, resisting co-governance might prove to be a matter of survival.

Decolonisation, in practice, amounts to white erasure. It’s not a sure thing that we will ever read the phrase “massacre of the remaining whites” in the context of New Zealand. However, it’s apparent that there are radical elements in New Zealand who would like to massacre whites, and that there are powerful foreign interests who would like to encourage such a thing in order to destabilise an enemy.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay/article, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles from 2021 from Amazon as a Kindle ebook or paperback. Compilations of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2020, the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019, the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 and the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 are also available.

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, subscribe to our SubscribeStar fund, or make a donation to our Paypal! Even better, buy any one of our books!

NZ will be decolonialized the same way South Africa was decolonialized. Its coming for sure. Roadmap was for it to be completed by 2040, just 20 years since Hepuapua was cooked up in secrete. I will be gone and I will spend my retirement poking fun at all the kiwis who kept their mouths shut for fear of being called racist. I just cant express my disgust at what Kiwis are letting happen to your country.