The New Zealand National Party has been a monolith on the New Zealand political scene ever since 1936, when it was formed to safeguard the privilege of ownership and to keep wages low. Its enduring and dominating presence is taken for granted by most, but not in this article.

In Sweden, the neo-Nazi Sweden Democrats have gone halfway to replacing the original right-wing party, the Moderates. Opinion polls since the last general election have mostly put the Sweden Democrats ahead. In several polls, the Sweden Democrats even scored higher than the Social Democrats, Sweden’s de facto ruling party.

In the Netherlands, a similar far-right-wing populist party, the Forum for Democracy, came from nowhere in 2017 to become the most popular party a year ago. They have since fallen back to around 10% support, but continue to pose a threat to the mainstream parties.

In Germany, a similar thing has happened, but on the opposite wing. There, the Green Party has grown to a higher level of support than the social democratic SPD, who have ruled Germany for 36 of the 75 years since World War II ended. The Greens are now the most popular party on the German left.

The reason why new parties in Europe are replacing the old ones is because the old ones have let themselves get horrendously out of touch with the peoples they claim to be representing. Young people on both the left and the right are deeply dissatisfied with their rulers. Immigration is one of the major causes of this dissatisfaction.

The social democrats in Sweden and Germany both played instrumental roles in opening the borders of those countries to mass Muslim and African immigration, a move that has had severe and lasting consequences for the young people already there. Given the enormous number of sex and violence crimes that followed, many of the most affected young people have started to look for electoral alternatives.

New Zealanders, whose experiences with immigrants have generally been much more positive than European people’s experiences with immigrants, don’t really care about mass immigration. But there are other ways in which the New Zealand ruling class have neglected the will of their people.

As generations shift, moral values shift with them. Old prejudices fall by the wayside; new prejudices arise. The National Party moved with the times when it came to hating Asians and homosexuals, but they clung to their hate for cannabis users. This is a function of both the large number of Christians within the National Party fold and the intensity of the anti-cannabis brainwashing that Boomers endured in school.

This small-mindedness is motivated primarily by cruelty, and National don’t pretend otherwise. It appeals perfectly to the grossly narcissistic and sadistic sentiments of the average Boomer. But, at the same time, it revolts the younger generations who don’t share the viciousness of the Boomers. This has created a demand for a right-wing alternative.

The ACT Party has a different approach to issues like drug law reform. They do not overtly appeal to malice like the National Party does. David Seymour’s policy book, Own Your Future, is generally positive towards cannabis law reform, if cautious. This approach is much more in line with the values of younger generations.

ACT already appeal to the younger generations more than National do. This was shown by Dan McGlashan in Understanding New Zealand. In this book, McGlashan found significant positive correlations between being in younger age brackets and voting for the ACT Party, as well as significant negative ones between being in those age brackets and voting National.

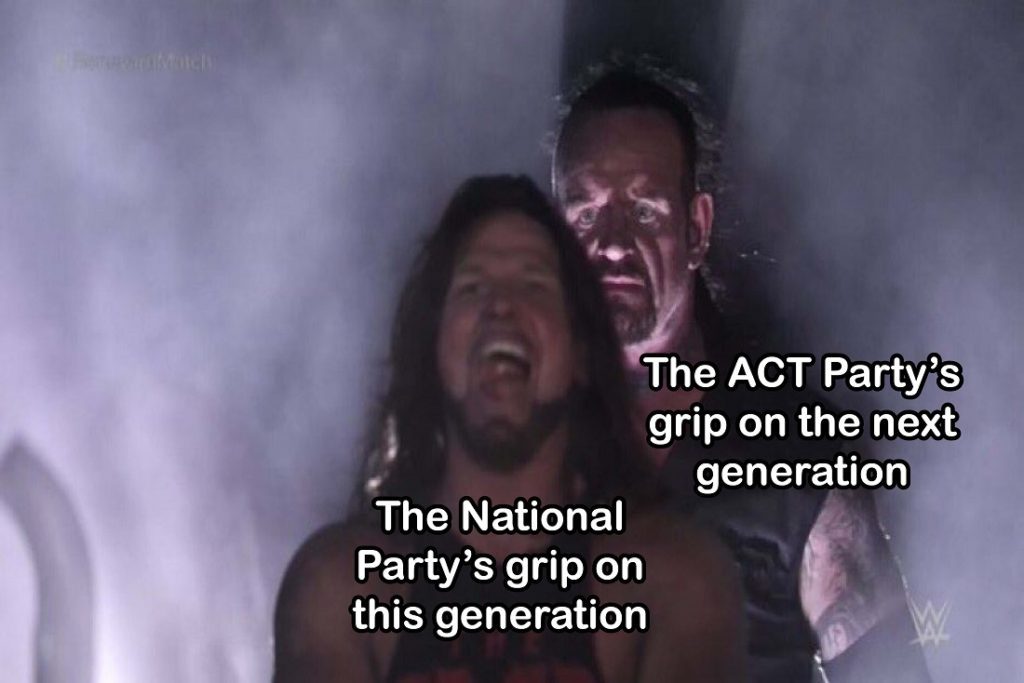

The right wing is split, between the older voters who prefer National and the younger ones who prefer ACT. The problem for National is that their voters are dying off, and the young ones aren’t necessarily switching to them from the ACT Party.

As time moves on, and as cannabis inevitably becomes legal and as people inevitably come to realise that the War on Cannabis was a complete waste of human life, voters will remember that National moved to perpetuate the suffering of the New Zealand people, and that ACT moved to end it. This will lead them to see National as the party of bad decisions, and ACT as the party of good decisions.

This has already started to happen to some extent. ACT have increased to 6% in recent polling, while National is scoring around 27%. This contrasts sharply with the 0.5% and 44.4% that ACT and National respectively scored in the 2017 General Election. ACT have gone up some 5.5% since then, while National have gone down some 17.4%.

There are many reasons for the change in fortunes, but one of the major ones is National’s refusal to accept the argument for cannabis law reform. This column has gone as far as to argue that National cannot win while it’s their policy to oppose reform. Stubborn support for cannabis prohibition appalls a large proportion of young people, and they see a clearly less appalling alternative in the ACT Party.

As time goes on, many of the young people who got in the habit of voting for ACT instead of National because of the cannabis referendum will continue to do so. This will lead to ACT taking an ever larger share of the right-wing vote. If the examples of Europe are anything to go by, it’s possible that this might continue until the ACT Party grows to replace National as the default leaders of the right wing.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 and the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 are also available.

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, please consider subscribing to our SubscribeStar fund. Even better, buy any one of our books!