Previous VJM Publishing articles have described something known as the electoral cycle. This is the process by which the right wing and the left wing of the ruling class take turns at ruling. In New Zealand, this is usually an 18- or 15-year cycle, and its continuation tends to bring political stability. But it’s starting to break down all over the Western World.

When the National/ACT/NZFirst coalition won the 2023 General Election, the expectation among most was that they would rule for their half of an electoral cycle, i.e. nine years. At the least, they would enjoy an extended honeymoon, as Jacinda Ardern, John Key and Helen Clark all did. The reality has been like a bucket of cold puke to the face.

Because of the electoral cycle, a New Zealand Government winning a second term has been a likelihood, and a third term very possible, ever since the end of World War II. But this can no longer be taken for granted. According to recent polling, the 2026 General Election will be very close. If New Zealand First dips below 5%, Labour would easily win that year.

If they do, the comfortable electoral cycle – which is ultimately based on trust and consensus – will have collapsed. Anyone could realistically fancy their chances for 2029: Labour again, National again, or anyone else.

The implications of an open field are tremendous.

For one thing, it could lead to the coming of a truly anti-Establishment force. Currently, anti-Establishment sentiments are channeled into New Zealand First, or absorbed into fringe movements like NZ Loyal and the ALCP. They don’t actually impact the Establishment or their operations.

If dissident voices felt like they actually had a chance to change things, on account of that the Labournational stranglehold was broken, they could enter the political stage in great numbers, and with great enthusiasm. A charismatic leader, backed by committed and competent people, could hope for 20% or more of the vote, as we have seen alternative movements achieve in some European countries.

For another thing, it will all but certainly lead to the further dissolution of support for mainstream politics. The strongest impetus for alternative politics is the sentiment that the Establishment doesn’t know what it’s doing. The political world is comprised of such sentiments. If (or when) the electoral cycle collapses, it would become widely realised that the masses no longer have much confidence in the Establishment. That would open the emotional floodgates to more support for alternative politics.

The collapse of this typical, conservative-to-social democrat electoral cycle has already been observed in some European countries. This has led directly to the 20%+ support for alternative politics mentioned above. In some cases there are multiple genuine alternatives. This is now the case in Germany, with the Alternative for Germany polling around 18% and the Sahra Wagenknecht movement polliing around 7%.

The ultimate theoretical implications of this collapse vary greatly. The Establishment’s Plan B would be to introduce a technocracy ruled directly by bankers, as they achieved in Italy under Mario Draghi. The intent of this plan would be to forestall the Establishment’s worst nightmare, which is that the people take their power back for themselves. A technocracy would avoid any real change.

Another possibility is a stagnation so deeply entrenched that it can only be overcome by a dictator. Once people stop supporting mainstream politics, many of them will stop supporting democracy. After all, the reasoning goes, if democracy only delivers us a choice between two wings of the Establishment, what good is it? If democracy led us to this, then what value is democracy?

If future polls suggest that Labour has a realistic chance of winning in 2026, then we can officially declare the comfortable post-World War II electoral cycle shattered, and the New Zealand political scene truly open for a change to the consensus – or at least a change to what the Establishment wants.

Where that might lead in practice is really anyone’s guess, but we can draw some reasonable conclusions from the examples of other Western countries, almost all of which share our dissatisfaction with the ruling establishment.

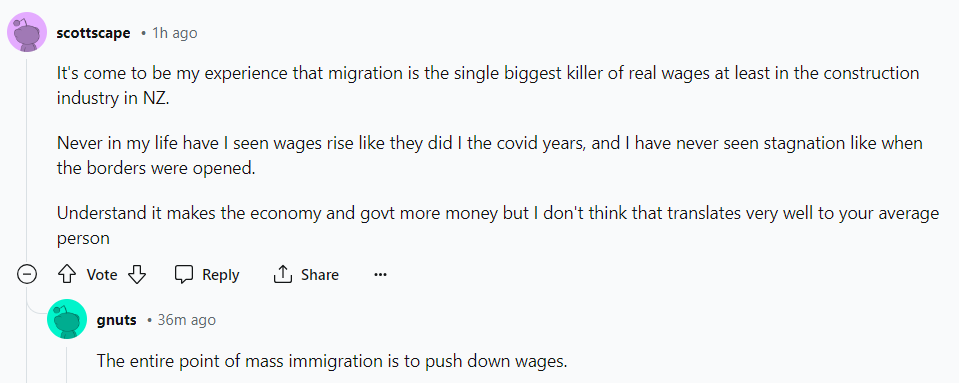

For one, it is likely to lead to a radical change to recent immigration policy. New Zealanders, like most Westerners, followed their mainstream media for decades when it told them that mass immigration would make us all wealthier. Now that the exact opposite has occurred, people are angry about having been lied to. Western rulers will be happy to blame outsiders if they can.

For another, it’s possible that it will lead to radical changes in housing policy. The Anglosphere has a tighter housing supply than other Western countries, which has led to the (intended) result of grossly inflated house prices. This has caused a commensurate amount of dissatisfaction among young people, who would love to redistribute some of the houses the Boomers have hoarded.

*

For more of VJM’s ideas, see his work on other platforms!

For even more of VJM’s ideas, buy one of his books!

*

If you enjoyed reading this piece, buy a compilation of our best pieces from previous years!

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2023

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2022

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2021

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2020

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, make a donation to our Paypal! Even better, buy any one of our books!