With every era that passes, old orders fall and new orders rise. Some of these old orders are military, some are technological and some are spiritual. With every Great Month that passes, a pre-existing spiritual order falls and a new spiritual order rises. This essay explains how we find ourselves now in such a time of change.

Some have described the changes upon us as the transition between the Age of Pisces, the old order, and the Age of Aquarius, the order to come. With the human entry into the Age of Pisces some 2,000 years ago, we moved out of the Age of Aries, which had been characterised by brutal militaristic sentiments. The Age of Pisces was, then, a reaction to the excesses of the age before it.

Pisces is the mutable water sign, which means that it has a double feminine energy. Arguably, the dominant spiritual ideology of the Age of Pisces has been Christianity, which also has feminine energies – it can be best understood as an attempt to reform Abrahamism from its brutal and hyper-masculine Arian frequency. Christianity has taken a watery form to counter the fiery nature of its predecessor, and the multiplicity of such forms reflects the mutable quality of Pisces.

In this Age of Pisces, people with this double feminine quality have done fairly well. This is not an age in which the strong conquer and dominate, but rather an age where the kind rule through the consent of the masses. The zeitgeist of the age has been to raise up those low down, and to pull down those up high.

Like everything else, however, it has become corrupted over time, and the form of it we now have is a degraded one. In its pure form, those unfairly cast down were lifted up, and those unfairly raised were pulled down. Now, a person is lifted up even if they were low down for natural reasons, or because of their own moral failings, while people who are high for just reasons are dragged down out of resentment.

It has been too long since the original spiritual revelations that began the Age of Pisces for them still to have power, and now a great counter-reaction against their present degraded forms is under way.

This means that the Age of Aquarius will involve a reaction against Christianity and against the ethos of passivity and agreeableness. Unlike the mutable water, the avatars of the Age of Aquarius will move ever-forwards. However, they will also be sure not to fall back into the patterns of the fiery ram-headed Arian aggression. Therefore, the Age of Aquarius will strike an airy balance between the watery Pisces and the fiery Aries.

Aquarius is the fixed air sign, which suggests a dogmatic and inflexible form of intellectualism. Combining this with the gentle masculinism of the age suggests that a kind of nerdiness might be the characteristic of coming centuries, perhaps an uncompromising kind of autism. This may be an outgrowth of today’s scientific materialism, the current dominant paradigm among the world’s ruling classes.

It might be that some kind of scientific materialism remains the dominant intellectual paradigm for the next 2,000 years, with all talk of the spiritual discouraged. It could also be that scientific materialism becomes the dominant paradigm for the ignorant masses only, while the enlightened and the initiated will be aware of the perennial truths that underpin the true philosophies of all times and places.

Certain phenomena predictably arise every time we near the end of a great age, as we now are. The foremost is a gross and paralysing apathy that drives all talk of the spiritual from public life. This can be seen with our current crop of atheistic rulers. However, this enormous apathy is necessary to wash away the vestiges of the old ways, and at its heart is the seed of a new spiritual order. The Age of Aquarius proper will begin when this new spiritual order begins to impose its will upon the world.

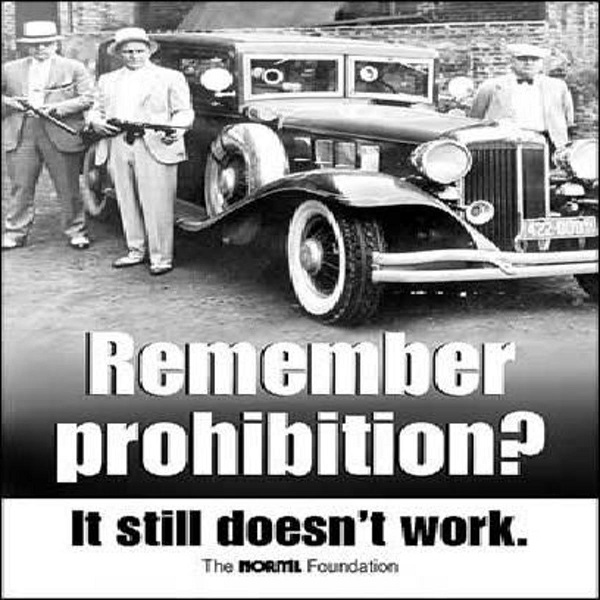

The first harbingers of this new spiritual order are those men and women who are rediscovering the spiritual sacraments that revealed the great wisdom that the ancients possessed. The vanguard of the new age of light returning to our benighted world is in those who have learned that psychedelics such as cannabis and psilocybin are capable of reconnecting a person to God and to the perennial wisdom.

There have always been small, clandestine groups of spiritual seekers who have kept the flame of genuine spiritual knowledge alive, despite the oppression from hate ideologies like Abrahamism, Nazism and Communism. These people have retained knowledge of the use of spiritual sacraments and techniques, even though the governments of recent decades have fought to suppress use of them. Most people now accept that the Governments are fighting a losing battle, so these groups have grown rapidly in number and influence.

However, it’s only now that a mass of people are starting to realise that these sacraments have revealed genuine spiritual knowledge to those brave enough to experiment with them. Bearers of light such as VJM Publishing are now able to publish information about spiritual alchemy without persecution – and we are far from the first or only ones. The spread of this knowledge will not stop until a new spiritual age exists upon the Earth.

It’s already possible to see magic mushrooms becoming legalised in places such as Denver. When magic mushrooms become legal more widely, it will become common for intelligent men and women to get together and use them sacramentally, to reconnect with God. When they do this, genuine spiritual knowledge will come to return to the Earth.

Although public sacramental use along the lines of the Eleusinian Mysteries are still some way off, in this general atmosphere of intellectual and spiritual exploration, it won’t be too long before there are some quasi-public rituals involving mass consumption of psychedelics. When this occurs, an entirely new consciousness will arise upon the Earth, involving new ways of relating to and identifying with each other.

If the Age of Aquarius means that scientific materialism completely destroys Abrahamism and the other superstitious cultures, this should clear the way for a return of those schools of thought that had been superstitiously attacked. This could very well lead to genuine spiritual revelation, and this could lead to a new spiritual era of human history and a new Golden Age.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 is also available.