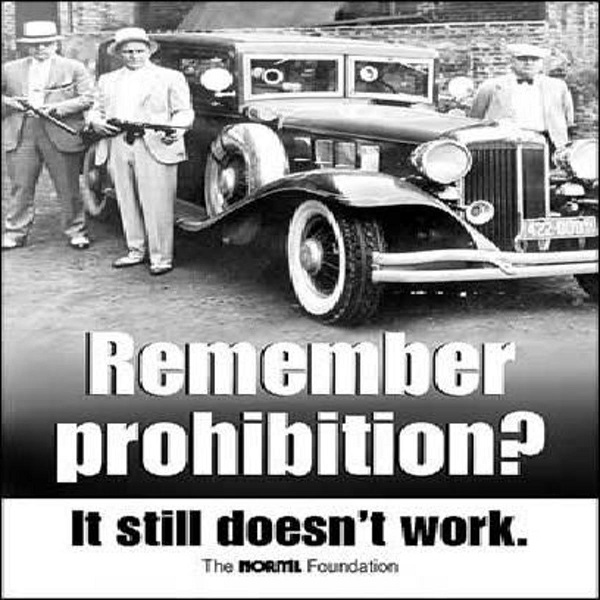

Although this book is full of arguments for cannabis law reform, all of them are technically forms of one great metaargument. All of the arguments for cannabis law reform, as the reader will discover, explore different facets of the failure of cannabis prohibition. This essay examines the fundamental argument at the core of the case for cannabis law reform – that prohibition doesn’t work.

Although there are a plethora of different kinds of cannabis law reform, all of them are based on the recognition that cannabis prohibition has a number of costs that could be saved. Although it’s denied by many, prohibition does have costs – the cost of law enforcement, the cost of prisons, the cost of faith in the Government, the Police and the medical establishment, among others.

Therefore, in order for this cost to be justified, cannabis prohibition has to do something good. There have to be profits somewhere to make up for all the costs. If there aren’t, then cannabis prohibition is a failed experiment and must be ended.

So let us ask: what is the objective of cannabis prohibition?

If the objective was to prevent people from using cannabis, that has failed. In 2008, 14.6 percent of the New Zealand population had used cannabis within the past 12 months, which is comparable to the prevalence rate of tobacco use. A decade later, cannabis is even more popular than before, and tobacco even less.

No intelligent person seriously believes that the law can override the people’s will to use cannabis. Exactly like alcohol prohibition, which failed to stop people from using alcohol, cannabis prohibition won’t stop people from using cannabis. Not only do people have a will to use it, but they feel that they have the right to do so. They’re going to keep using it forever.

If the objective was to protect people’s mental health, that too has failed. Not only is there no correlation between rates of cannabis use and prevalence of mental illness on the national level, but there is ample scientific evidence that cannabis does not cause psychosis or schizophrenia. The cannabis-psychosis link is best explained by the fact that cannabis is medicinal for many mentally ill people, and so they seek it out.

Instead of protecting people’s mental health, cannabis prohibition leads to the further social isolation of cannabis users by making them unwilling to speak candidly to mental health professionals, or to their friends or workmates. If cannabis is illegal, then confessing to using it is tantamount to confessing to criminal activity, so many mentally ill people who need help would rather just sit in silence.

If the objective was to protect children from psychoactive drugs while their brains are still developing, that too has failed. Because cannabis is on the black market, and therefore sold by criminals, there is nothing in the way of age checks between young people and the cannabis supply. Gang members will happily sell bags of cannabis to 12-year olds if they have the cash.

People often make the “think of the children!” argument when it comes to cannabis law reform, but the simple fact is that prohibition makes it easier for minors to get hold of cannabis. Proof for this is as simple as asking a minor if it’s easier to get hold of alcohol or cannabis. They’ll tell you that it’s harder to get hold of booze because those selling it are serious about keeping their liquor license.

If the objective was to instill respect for authority, that’s completely backfired. Cannabis prohibition is so stupid an idea that the people at large have lost respect for those pushing at and those enforcing it. Although the idea that one’s politicians are stupid and evil is far from new, these sentiments become problematic when they’re applied to other segments of society. Prohibition, however, makes this all but inevitable.

Many New Zealanders have now come to feel that the Police are their enemy, because Police officers have shown themselves willing to confiscate people’s medicine and to imprison them for using it. Far from being the trusted community servants that they are seen as in places like Holland, they’re seen as enemy soldiers waging an immoral war against an innocent people. To a great extent, this is the fault of cannabis prohibition.

All of these arguments (among others) are discussed at length in the various chapters of this book, but they all support the central thesis – that cannabis prohibition doesn’t work. It doesn’t achieve its stated aim of reducing the sum total of human suffering, and if it doesn’t achieve its stated aims, then it isn’t justified to continue with it any longer.

The men who pushed cannabis prohibition on a naive and unsuspecting public almost a century ago are now dead. Whether they knew they were speaking falsehoods or whether they were genuinely misled is no longer material. The right thing for us to do is to assess reality accurately, so that we can move forward in the correct direction.

If we look around the world honestly, it’s obvious that prohibition has failed. Not only is cannabis culture thriving, even in the most unlikely places, but support for cannabis law reform is rising almost universally, across all nations and demographics. The most striking sign is the ever-increasing number of states, territories or countries that have recently liberalised their cannabis laws.

The cynic might say that this is an example of the bandwagon fallacy, but that is not an accurate criticism. The reason why so many countries are changing their cannabis laws is because the evidence against cannabis prohibition has now mounted so high that it can no longer be ignored. There are now many countries liberalising their cannabis laws for the simple reason that the evidence suggests that it’s a better approach.

Cannabis prohibition simply doesn’t work. There is nowhere in the world that has prohibited cannabis and observed any result other than more poverty, distrust, misery and hatred. It’s fundamentally for this reason that the cannabis laws ought to be reformed.

*

This article is an excerpt from The Case For Cannabis Law Reform, compiled by Vince McLeod and due for release by VJM Publishing in the summer of 2018/19.