A common prohibitionist double-whammy is to argue that cannabis should remain illegal because, if it were made legal, people would use it more, and because its use is harmful, legalisation would therefore lead to more harm. This article will not argue whether cannabis is harmful (this is done elsewhere), but will simply summarise what the evidence suggests: that legalisation will not increase rates of cannabis use.

It seems intuitively obvious that making cannabis illegal lowers the rate of cannabis use. After all, the whole point of making it illegal was to make it harder to get, and if it were legal people would be able to buy it from shops.

Fair enough, but the statistics show a different story.

The truth is that cannabis cultivation is so common (believed to account for 1% of electricity consumption) that pretty much anyone who wants to get hold of it can, except for times of unusually high demand. This means that the cannabis market is already saturated – and this can be demonstrated with reference to real-world examples.

The most obvious counterpoint to the argument that legalising cannabis will increase rates of use is the fact that rates of cannabis use are not higher in places where it is legal.

In the Netherlands, 8% of the adult population has used cannabis at some point in the last 12 months. This rate is lower than in Australia (10.6%), where cannabis is illegal, and much lower than in New Zealand (14.6%), where cannabis is also illegal. In countries such as Israel and Ghana, the rate of cannabis use is higher still. Cannabis might not be technically legal in the Netherlands, but in practice anyone who wants to buy it from a shop can do so.

If legalising cannabis will inevitably cause rates of use to increase, how can it be possible that rates of use are lower in a place where it is legal, where getting supplied is as simple as walking into a shop? If the link between cannabis being legal and higher rates of cannabis use is so certain, we could expect to see higher usage rates in all the places where it is legal, and lower usage rates in all the places where it is illegal. In reality, any such correlation is hard to discern.

The truth is already known to anyone who has ever been to the Netherlands. Cannabis is easy to get hold of, yes, and the Police won’t harass you for it, that’s true, but the bulk of the population would rather drink alcohol anyway. Cannabis law reform didn’t turn a large number of non-drug users into cannabis users – a small number of alcohol users became cannabis users, and the rest stayed the same.

The absence of a correlation between the legal status of cannabis and the rate of use within a jurisdiction is not the only place that statistics disprove the idea that legalisation will lead to more cannabis use.

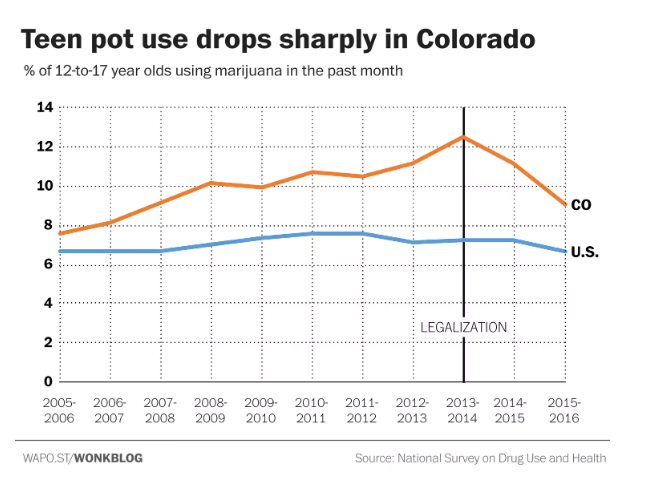

A poll by the Colorado Department of Public Health found that cannabis use rates declined among teenagers after legalisation, with rates of teenage use in Colorado lower than the American national average. Another study, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, supports the idea that teenage cannabis use rates actually declined after it was made legal.

In fact, the latter study suggests that teen cannabis use rates declined in the majority of states that recently made cannabis legal. It may be, as some have suggested for decades, that the Government lying about the effects of cannabis and exaggerating its dangers was what led to many young people becoming attracted to it. Had there never been an unjust law prohibiting cannabis, it’s possible that the rebellious section of society would never have felt obliged to defy it.

At this point it could be countered that, even if teenage usage rates of cannabis go down, and even if this was the most important thing, adult rates of cannabis use might still increase if cannabis were legalised, and that this might lead to more harm. Leaving aside the fact that this argument has already been countered in the first part of this article, it doesn’t even apply here.

There is little doubt that some people will replace recreational alcohol use with recreational cannabis use if it were legal to do so. Technically, this would mean that the rate of cannabis use would increase, but the rate of recreational drug use would remain the same. Moreover, the rate of harm caused by recreational drug use would decrease if some people replaced boozing with cannabis, on account of that alcohol is more harmful.

Ultimately, the argument that cannabis legalisation would lead to more suffering through increased rates of cannabis use is in error, for multiple reasons. A review of the statistical data shows that cannabis use is not higher in places where it is legal, and also that rates of teen use have declined in American states that have made it legal.

*

This article is an excerpt from The Case For Cannabis Law Reform, compiled by Vince McLeod and due for release by VJM Publishing in the summer of 2018/19.