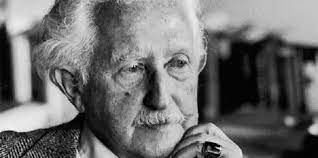

Psychologist Erik Erikson is best known for his theory on psychosocial development, which outlines the various stages of development and highlights their key characteristics and associated conflicts. However, another area that Erikson extensively researched was early childhood trauma and its effects on healthy psychological development.

Early childhood trauma refers to any adverse event or experience that a child experiences before the age of six. This can include various forms of abuse, neglect, loss of a loved one, violence and other experiences that can negatively impact a child’s healthy psychological development. Erikson was keen to address the effects of such trauma on child development, noting how they can affect an individual’s psychological makeup well into adulthood.

One of the key areas of early childhood development that Erikson focused on was the development of trust versus mistrust. According to Erikson, children pass through this stage within the first 18 months of their life, and its central conflict is between trust and mistrust. In this stage, children require consistent care and affection from their primary caregivers to develop a sense of trust in the world around them. Parents and caretakers play a crucial role in shaping the child’s perception of the world through their daily interactions and responses to the child’s needs. If these needs are not met due to early childhood trauma, mistrust may develop, leading to further psychological problems later on in life.

Erikson also emphasized the importance of a child’s autonomy during the second stage of psychosocial development, which occurs between the ages of two to three years. This stage is marked by toddlers’ assertion of their autonomy as they seek to assert control over their immediate environment. Children who experience early childhood trauma may find it challenging to develop a sense of self-trust and autonomy, leading to lower self-esteem, anxiety and feelings of inadequacy that can be long-lasting.

Early childhood trauma can also have profound effects on a child’s social and emotional development, affecting their ability to form secure relationships and attach healthily to others. Erikson posited that children pass through the stage of intimacy versus isolation during young adulthood, where they seek to develop genuine connectedness with others. However, individuals who lack a sense of trust and self-autonomy may find it difficult to establish such connections, leading to social isolation and feelings of disconnect.

Erikson was also concerned about the effects of early childhood trauma on academic achievement, given its critical role in shaping later-life outcomes. He argued that children exposed to traumatic experiences may develop cognitive and behavioural difficulties that can hinder their academic progress. Such difficulties can have long-lasting effects on their future career prospects, social mobility and overall well-being.

One of the most severe consequences of early childhood trauma is the risk of developing mental health issues such as anxiety or depression. This is because such experiences can leave a lasting impression on a child’s psyche, leading to unresolved emotional conflicts and feelings of vulnerability. The effects of childhood trauma can manifest in adulthood, leading to the development of low self-esteem, trust issues, difficulty forming relationships, and a host of other psychological difficulties.

Erikson was keen to emphasise the role of caregivers and parents in providing support and guidance to children exposed to early childhood trauma. Through supportive care, counseling and therapy, individuals can better work through such traumas and minimise their impact on their psychological development.

In conclusion, Erikson extensively researched the effects of early childhood trauma on healthy psychological development, noting how it can negatively impact a child’s perception of the world and their place in it. From issues of trust versus mistrust, autonomy, academic achievement, and social-emotional development, early childhood experiences profoundly shape later life outcomes.

Caregivers and parents play a crucial role in providing support and guidance to children experiencing traumatic events, which can minimise the impact of such events on their psychological well-being. Erikson’s work reminds us of the importance of a supportive and nurturing environment for children to develop healthy psychological development and highlights the long-lasting consequences of early childhood trauma.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay/article, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles from 2021 from Amazon as a Kindle ebook or paperback. Compilations of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2020, the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019, the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 and the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 are also available.

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, subscribe to our SubscribeStar fund, or make a donation to our Paypal! Even better, buy any one of our books!

Dr Arthur Janov, who worked with the traumatised all his life, once said “Often it’s the rebellious child who is halfway a human being, and the good child who has been completely destroyed”.

And this was not his theoretical speculation, but a more direct observation with his patients, whose trauma was truly broken down – allowing them see ‘before and after’ impacts.

Erickson does not understand what normal really is. He naturally assumes his normal, is normal. Alas, did you know that children born truly non-traumatically are mostly ambidextrous? And you thought having a had dominance was normal, lol. Nope – not really.

We are not a “normal” society at all. We still have a very long way to go and many levels.

> did you know that children born truly non-traumatically are mostly ambidextrous? And you thought having a had dominance was normal, lol. Nope – not really.

I had no idea, that’s fascinating to think about. If handedness is a trauma response, what else could be?

Yep. Many things will be a trauma-response that we don’t yet recognise as being that. It’s hard to know what ‘normal’ is, when nearly everyone is damaged in the same way – as we are.