When the pension system was introduced in New Zealand in 1898, the average life expectancy was less than 60. Today, it’s closer to 80. Consequently, pension expenses have ballooned. This article discusses whether New Zealand should lower the pension to bring it in line with other main benefits, and what we could afford if we did.

A lot of words are being written lately about universal basic income, but few realise New Zealand already has a universal basic income for the over 65s, known as National Superannuation.

The argument for paying out this universal benefit is that people older than 65 cannot reasonably be expected to earn a living through the workforce, and therefore would starve without a pension. That seems entirely fair. Not many people would argue that a person should be forced to starve, in this age of plenty, just because they were too old to work.

However, the amount of money paid in pensions is taking the piss. $360 per week to every person over 65, when a majority of them own their own house, is an obscenity, when we expect severely mentally ill people to survive on $273 per week, out of which they almost always have to pay rent.

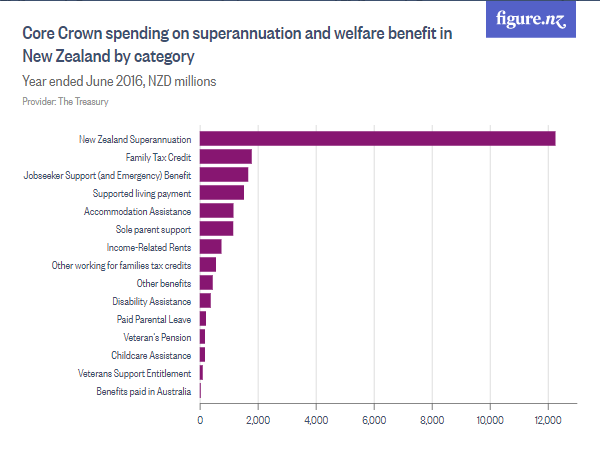

As of June 2019, the New Zealand Government spends over $12,000,000,000 every year on pensions (see table at top of article). This mostly consists of the $20,000 of yearly pension payments per recipient, multiplied by the 600,000+ eligible pensioners in New Zealand. Pension spending is projected to be $20,000,000,000 by 2031.

Although most people can agree that it’s cruel to leave people to starve on account of that they’re too infirm to work, there’s no reason for the Government to be granting pensioners a lifestyle that compares with what people make from working. Indeed, if they’re not working, why should they be paid any more than the unemployment benefit?

A fair compromise between the current luxury pension model on the one hand, and reducing the pension to the level of the unemployment benefit on the other, might be to reduce the benefit to a midway level. This would recognise both that current pension spending is an unsustainable and unfair burden on the under-65s, and that the infirmity of old age demands more expenses than the health of youth.

If the pension was cut by 25%, from its current $360 per week to around $270, this would bring it in line with other main benefits such as the Supported Living Allowance. This 25% reduction would equal a savings of $3,000,000,000 per year in pension expenses.

To give an example of how much money that is, it’s roughly equal to the $3,000,000,000 in tax revenue that the Government gets from the 10.5% tax on the first $14,000 of income. This tax works out to slightly less than $1,500 per person for each of New Zealand’s roughly 2,000,000 wage or salary earners.

So lowering the pension by 25% to bring it in line with other main benefits could be balanced by making all income up to $14,000 tax free. This would be a revenue-neutral move – there are plenty of other ways to spend $3G, but this would be one of the most popular.

Introducing a $14,000 tax-free threshold would make two million New Zealanders much happier about going to work every day. It would revitalise the workforce by giving every worker an extra $1,500 per year. This works out to almost $30 per week. That would make a huge difference to standard of living given the cost of living and cost of housing at the moment.

For two-parent families, such a saving would equal roughly $60 per week. For many Kiwi families on the breadline, this would be enough money to make the difference between survival and disaster some weeks.

There’s no loss to bringing this in, apart from a reduction in luxuries for our current crop of pensioners. None of those pensioners will go hungry because they would still get as much as an invalid’s beneficiary, and considering that these same pensioners had the luxury of being able to buy a house on one income – a luxury that younger generations will never have – there’s no reason for the rest of us to spend empathy on them. We ought to keep it for each other.

At the moment, New Zealand is being sucked dry by a cohort of super-entitled Baby Boomers who feel that they have the right to party it up for 20 years after they reach 65. This was only sustainable when pensioners were a small percentage of the population, but with as much as 20% of the population soon wanting a slice of the pension pie, it no longer is.

We need to bring the pension in line with other main benefits in order to rein in our bloated Superannuation expenses. Reducing it to the same level as the Supported Living Allowance would free up roughly three billion dollars every year. Freeing our economy from this burden would make life a lot easier for the vast majority of Kiwis.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 is also available.