The West is in a dismal state today. Despite unprecedented material wealth, our collective social capital has never been lower. Sometimes it feels like the West is in a state of civil war, with chaos and destruction reigning in many major cities. Most of this was predicted at least half a century ago, by those who studied the demographic trends.

The American fertility rate was over three children per woman from 1950 to 1964. This period of high fertility became known as the “Baby Boom”. The rate fell sharply after 1964, and by 1978 it had fallen to 1.8 children per woman. This demographic pattern had serious economic consequences.

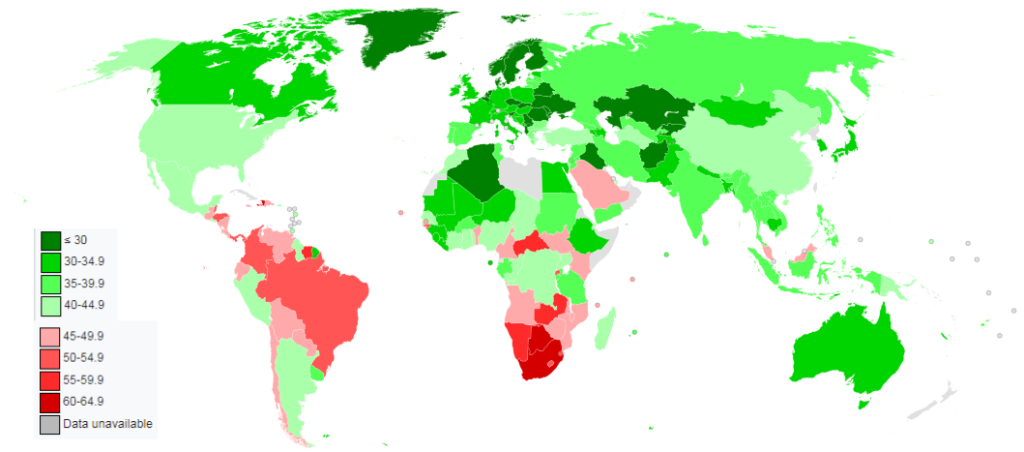

As the Boomers entered the workforce en masse, an incredible economic phenomenon began. Because there were a great number of workers, and very few elderly or young dependents, the economy was unusually profitable. This is measured by something called the dependency ratio, which is the ratio of people in the workforce to people not in the workforce.

The dependency ratio was high during the Baby Boom, on account of all the children, but it began to plummet from around 1980, after those children entered the workforce. This led to a time of great profitability, which lasted as long as the Boomers were in employable age groups.

By today this process has begun to reverse. The first of the Baby Boomers hit the pension age of 65 in 2010. Ever since then, the dependency ratio has risen. In 2000, there were five workers per pensioner in America; by 2050, there are expected to be 2.9 workers per pensioner. We are about to go through a time of great unprofitability.

The saying “demography is destiny” refers to the fact that the macrotrends of Western economies since World War II have followed demographic trends.

When the Boomers die off en masse, a process which is beginning now, the dependency ratio will improve. This will also lead to a sharp decrease in housing demand. The combined effect of these two major changes will create an economic boom lasting several decades. Unfortunately for most of the people reading this article, the post-Baby Boomer boom won’t fully start happening until after 2050.

The situation might seem bad for the West, but it’s even worse in the industrialised countries of the Far East. Their fertility rate collapse is a more extreme version of the Western one.

China had a similar economic boom to the West from 1985 to 2010, with a large demographic bulge of working-age people keeping the dependency ratio low. But China today, despite being infamous for its population, only has a fertility rate of 1.7.

In 2010, the old-age dependency ratio in China was 11%, meaning nine workers for every pensioner. By 2060, it is expected to be over 50%, meaning two workers for every pensioner. Considering that they are only a middle-income nation today, and that future economic growth is uncertain, a dependency ratio of 50% threatens to cause extreme poverty.

It’s worse still elsewhere in Far East Asia.

In 2020, the South Korean fertility rate is less than 1.1 children per woman. At a fertility rate this low, the South Korean population will halve every generation. The fertility rates of people in Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan are only slightly higher, around 1.4. Their populations should decrease by a third every generation. China’s should decrease by a quarter.

Some might argue that Europe and Far East Asia are overpopulated anyway, and the environment would benefit from a sharp population decrease. The trouble is that the rulers of both places are accustomed to a certain standard of living, and, if given the choice, will act to maintain that standard of living even if succeeding generations have to suffer for it.

In Western countries, falling populations have been preempted by mass immigration. This has prevented Western economies from shrinking, keeping stock prices and house prices high, and the ruling class happy. However, the result of this process has been the collapse of social cohesion, reflected everywhere in less trust.

A nation that opens itself to mass immigration also opens itself to division and, eventually, chaos. The historical record is clear on this subject, as is the science. Changes in kinship intensity have direct and far-reaching political consequences. If demographics lead to a decrease in a nation’s kinship intensity, then that nation’s destiny is discord and war. The civil unrest in today’s America is merely a foretaste.

That demographic trends are capable of tearing nations apart from the inside can be understood mathematically. Taking the example of France, it can be seen that the destiny of any population with a low fertility rate, once it comes to host a foreign population with a high fertility rate, is to be conquered.

If the white population of France is 50,000,000, and their women reproduce at the rate of 1.5 children per woman, the white French population will fall to 28,125,000 after two generations. If the Muslim population is 5,000,000, and their women reproduce at the rate of three children per woman, the Muslim French population will rise to 11,500,000 after two generations.

After three generations, the French population will be some 21 million, and the Muslim population some 17 million. By that time, the majority of fighting-age males will belong to the Muslim population, and France will be a de facto conquered land. Muslims will have achieved with their wombs what they could not achieve with their swords 1,300 years earlier, at the Battle of Tours.

Much the same logic was followed by French financier Charles Gave, who outlined it in a paper he wrote for the Institute of Liberty. He was immediately attacked for promulgating the great replacement conspiracy theory, only it is no conspiracy. It’s a simple extrapolation from currently known values, and its logic is inescapable.

The fertility rate in France has been famously low for over a century now. The fertility rate in neighbouring Algeria, by contrast, was over seven children per woman as recently as 1980. The consequence is that, by today, there are two to three times as many Algerians in France as there were French people in Algeria in 1940, when Algeria was a French colony. France is now itself a colony in all but name.

France’s destiny is to become an Islamic state. This follows inexorably from their current demographics, and is no harder to predict than was the German victory over France in World War II. This victory had been forecast over half a century beforehand, by people who knew that Germany had a much higher fertility rate than France, and who had calculated that this would eventually lead to an overwhelming German numerical advantage.

The single most important demographic trend of this century is the one that predicts that the population of Africa will quadruple by the end of the century. Currently around one billion, it is expected to be four billion by 2100, which will mean that almost half of the world’s population will be African.

Countries like Niger and Somalia are still reproducing at the rate of over six children per woman. The total African fertility rate is 4.4 children per woman. The sad reality of this population explosion is that, by the end of this century, the majority of Africa’s megafauna will be extinct in the wild. Most megafauna are already threatened thanks to human population pressure, and they will not survive an African population of four billion.

The societies of Europe are unlikely to survive it either. Europe today is barely capable of defending their borders against migrant inflows from the South. In the medium-term future, with an even smaller European population and a surging African one, they won’t be capable of defending them at all. The destiny of Europe appears to be getting overwhelmed by the surplus African population.

The next century looks like it will bring a drastic decrease in the high IQ populations of the world, and an equally drastic increase in the low IQ populations of the world. The inevitable result will be low IQ people surging into high IQ territories, and a profound increase in the average amount of human suffering. Demography really is destiny, and it suggests that the world’s destiny is a grim one.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 and the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 are also available.

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, please consider subscribing to our SubscribeStar fund. Even better, buy any one of our books!