The aftermath of the Christchurch mosque shooting showed that the New Zealand Government is willing to give away all of our freedoms in its blind panic to clamp down on everything. We Kiwis are going to have to learn how to fight Internet censorship and how to share information despite a Government committed to banning free discussion. This article discusses the basics of VPN use.

‘VPN’ stands for Virtual Private Network. It serves to extend a private network across a public one, so that you virtually access a private network somewhere else in the world. Essentially, a computer somewhere else surfs the Internet on your behalf, and then sends the data directly to your computer. The point of this is primarily to circumvent government censorship and corporate geo-restrictions.

It’s like the diplomatic black bag of internet traffic – the Government can’t snoop in on it while its in transit and choose to block it.

VPNs are very popular in totalitarian countries such as China, because they allow their users to access websites that the government doesn’t wish them to access. As any reader of 1984 could tell you, the prime objective of any government is to stay in power, by whatever means necessary. One of the primary ways this can be achieved is by controlling information and discourse, so that rebellious ideas cannot flourish in the minds of the populace.

As Joseph Stalin put it: “Ideas are more dangerous than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas?”

In the wake of the Christchurch mosque shootings, the New Zealand Government has taken a sharply totalitarian turn. They seem to have decided, without securing the consent of the people or even making an announcement, that it’s okay for them to censor whatever website they see fit, for any reason (or even none). Although they will not admit it, this is a totalitarian action that breaches fundamental human rights. For this reason, we citizens are forced to take counter measures.

When a country such as New Zealand tries to block the free flow of information to its citizens, those citizens have to turn to grey- or black-market solutions such as VPNs. Using a VPN will allow a person to access almost any website that the New Zealand Government may have decreed verboten, for the reason that the Great Firewall of New Zealand will consider the web traffic to be something else.

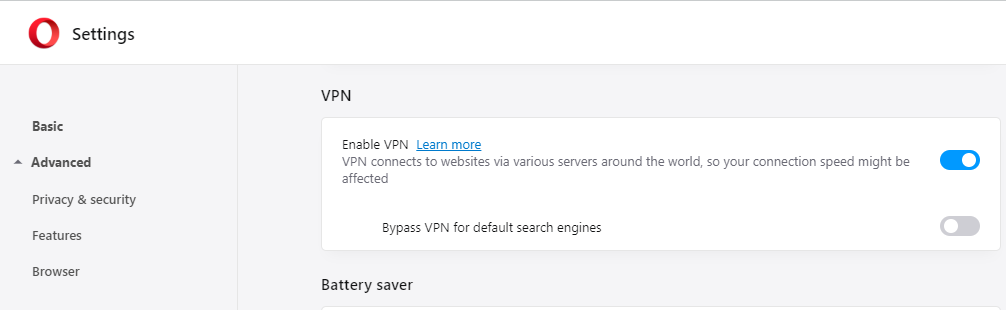

The Opera browser comes with a built-in VPN, which is probably the easiest way to get started for anyone new to the idea. The simplest way to get started is to just download and install the Opera browser (the download page can be found with a simple web search). If you then open that browser, you can see the Opera symbol up in the top left corner. Clicking on this will open a drop-down menu, on which you can select ‘Settings’ near the bottom.

This will take you to a separate Settings page, where you have a number of options. By default, you will come to the Basic panel. Towards the top-left corner of the screen, underneath the word ‘Settings’ you should be able to see the words ‘Basic’ and ‘Advanced’. ‘Advanced’ is a drop-down menu, itself consisting of three options: ‘Privacy & security’, ‘Features’ and ‘Browser’.

If you click on ‘Features’, a number of options will appear in the centre panel. At the top of these is one called ‘VPN’. Underneath this is the option to ‘Enable VPN’. From here, enabling the browser VPN is a simple matter of hitting the radio switch to the right.

Note that this may make your browsing a bit slower, because the VPN is an extra step between you and your data. However, this is a minor inconvenience, and may be your only easy option if you want to access forbidden websites.

Some people might say at this point “But the Government, in its omnibeneficence, only banned the really evil sites where hate speech flourished and I didn’t want to go there anyway.” Fair enough – but the Government could ban anything else in the future, and so you might as well learn how to circumvent that now while you still can.

Ask yourself, do you really believe that the Government is going to stop with 8chan and Zero Hedge? The Government probably regrets that the Internet ever came to exist. They would gladly switch to having a North Korea-style government news service with all alternatives banned if they thought they could get away with it.

So what we can expect is more of what David Icke calls the “Totalitarian Tiptoe”, in which the Government bans an ever-increasing number of websites, taking advantage of moral panics to do so. Because the Government’s appetite for power and control is unlimited, Kiwis ought to get to know the basics of VPN use immediately.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 is also available.