In this age of tyranny and chaos, many people have lost their natural understanding of the inherent rights of human beings. Many of us have strayed so far from reality, and drifted so far into slave morality, that we honestly believe that rights are granted by the goodwill of the Government. This essay will argue that human rights are not only inherent, and necessary for any civilisation to exist, but also that they are sevenfold, at three different levels of resolution.

To understand our inherent rights, it is necessary to turn to a philosophy that accurately describes reality. We do so here with reference to elementalism, in particular the hierarchy of the four masculine elements. The four masculine elements are clay, iron, silver and gold, in ascending order of rarity and value.

Clay is the most fundamental of the masculine elements, and represents the feminine realm of Nature. In this sense, it represents the rights relating to a person’s life, their right to life and their right to self-ownership. Inherent human rights in the realm of clay means that people inherently have the right to life.

Applying the paradigm of clay to human rights tells us that the State does not have the right to kill its citizens, and neither may it claim right over a person’s body without that person’s consent. The Government may not use the people for medical experimentation, and neither may they be conscripted, whether as soldiers or labourers.

More specifically, the Government ought not to levy taxes on basic food produce, and neither should they interrupt the right of people to gather food and water from the wilderness, because both processes are essential for life. Some would go as far as to argue that the State ought to supply a universal basic income to compensate for the imposition of private property.

Iron is the next most fundamental element, and refers to the masculine realm of war and defence. Inherent human rights in the realm of iron means that people inherently have the right to physical self-defence. They have the right to own and carry weapons, both to protect their own person and their home. They also have the right to expect that the State will act to defend the physical integrity of the nation, and that it will act to protect their private property.

It is also recognised here that the people themselves are the ultimate guarantor of their rights. The realm of iron is the realm of masculine wisdom, and here it is understood that the Government is not always the friend of the people, and is all too often its enemy. Being wisdom, and not excess, there are limits here: people may only harm others if those others are posing a direct, immediate and actionable threat.

Anarcho-homicidalism is enshrined as a right under the realm of iron. The people are never obliged to be slaves – this right is absolute and fundamental. Therefore, they have the right to take any measures necessary to resist enslavement – up to, and including, killing their enslavers. The point at which it is necessary to do so is a question for the people themselves, and never a question for their government.

Silver is the first of the precious masculine elements, and refers to the realm of the mind and intellect. Inherent human rights in the realm of silver means that people inherently have the right to pursue and to discuss the truth. This is otherwise known as the “right to free inquiry” because it is in the nature of gentlemen, when their baser duties are discharged, to discuss such things.

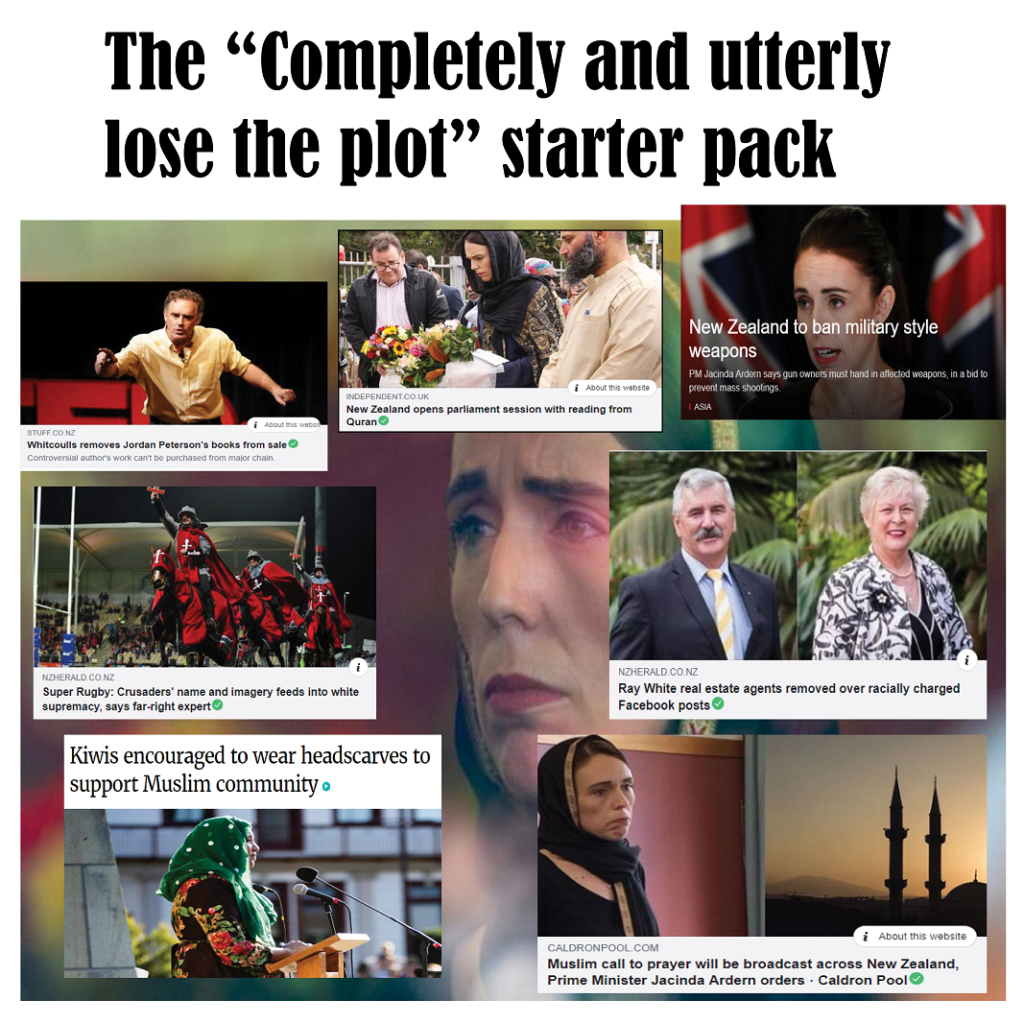

This implies that the rights of the people to freely research, read, discuss and impart information shall not be restricted, except in cases where there is an immediate risk of physical suffering (i.e. incitement of violence). People must always have the right to gather to discuss subjects and to impart information to each other. The State has no right to interfere with a person’s life because they expressed a certain piece of information, whether fact or opinion.

These rights mean that institutions like the Office of Chief Censor are to immediately be abolished. Nothing is to be censored, however certain information might be classified as unsuitable for some audiences, in that exposure to it may cause them harm. Note that, with the realm of iron, there are limits to rights here: the right to free speech does not legalise fraud, nor outright lying for the sake of defamation.

Gold is the most precious of the masculine elements, and refers to the realm of consciousness and God. Because God is more fundamental than language, and therefore cannot be spoken of, it’s not easy to speak about what inherent rights a person has in the realm of gold. Like gold, these rights are precious, and sometimes very rare. In principle, the paradigm of gold here relates to the rights to religious and spiritual freedom.

Inherent human rights in the realm of gold means that people inherently have the right to conduct any ritual, and to consume any spiritual sacrament, that they believe will get them closer to God. These rights are subject to the three more fundamental rights, in that they cannot infringe on any other person’s free speech (i.e. no blasphemy laws), they cannot infringe on any other person’s bodily integrity (i.e. no infant genital mutilation) and they cannot infringe on any other person’s right to life (i.e. no convert or die).

This means that the State has absolutely no right to restrict the consumption and sharing of spiritual sacraments such as cannabis, psilocybin and DMT. No-one has to go through a court and argue that these substances are part of any recognised religious tradition – they simply have the inherent right to use them. Citizens inherently have the right to take any action they feel will bring them closer to God, as long as it does not cause suffering to others.

It is also recognised here that rights are granted by the Will of God, which is more fundamental than the right of any human institution, whether governmental, ecclesiastical, military or otherwise. Therefore, because these rights are granted by God, no such institution can rightly take them away. If it tries to, the people have the right to resist, and they have God’s approval to do so. These rights are inherent to the nature of reality, which is something more fundamental than human governments.

There is another layer behind these four masculine elements. It could be said that, in the same way that the four masculine elements divide into base and precious, so too do our rights divide into a base right that can easily be understood by all people, no matter their intellect, and a precious right that that is harder to grasp but which must be fought for with a determination befitting its value.

The fundamental feminine right, then, relates to the physical world. It is the right to not suffer physically at the hands of the State; the right to physical liberty. What this means in practice can be seen be examining the realms of iron and clay. We can summarise it as the right to bodily integrity, or the right to not have one’s bodily integrity harmed by the State.

The right to physical liberty means that people have the fundamental right to decide how their bodies are used, and what goes into them, and what stays in them – this is known as the Base Right because even animals intuitively understand it. The State does not have the right to impede the physical security or harm the physical integrity of its citizens, whether at the group or individual level. Neither does it have the right to impede their access to territory, unless suffering should be caused by doing so.

In practice, this means that the State does not have the right to interfere with the reproductive rights of its citizens. It cannot mandate a limit to family size, for example, and neither can it prohibit abortion. Nor can it force vaccinations on people, or any health treatment on people, without their consent – the Base Right forbids it. It also means that people, at the group level, have the right to free assembly.

The fundamental masculine right, on the other hand, relates to the metaphysical world. It is the right not to suffer metaphysically at the hands of the State. What this means in practice can be seen by examining the realms of silver and gold. It can be summarised as the right to metaphysical integrity, or the right to not have one’s metaphysical integrity harmed by the state.

In much the same way that people have the right to decide what goes into their bodies and how their bodies are used, they also have the right to decide what goes into their minds and how their minds are used. This right is called the Precious Right because, like masculinity itself, it isn’t always clearly understood.

It means that people have the right to cognitive liberty. Although much of this is already covered under the realm of silver and its rights to free speech, there is more here. The State may not infringe on the rights of the people to express themselves, and may not interfere with the psychological integrity of its citizens, whether at a group or individual level. Neither may it decide that certain practices are legitimate spiritual ones and others not.

There is a third and final level, a right even more fundamental than the Base and Precious Rights, the seventh right that ties all the others together. It is, simply put, the right not to suffer at the hands of the State. This is known as the Fundamental Right and is to be used as the guiding principle whenever it is not clear how to proceed.

The right not to suffer at the hands of the State underpins all of the Base Right, the Precious Right, the right to life, the right to self-defence, the right to free inquiry and the right to spiritual exploration. The Fundamental Right recognises that the State may not cause suffering to people in any of the physical, metaphysical, spiritual, intellectual, martial or biological realms.

Describing our rights like this, in elemental terms, is now necessary owing to the confusion that has arisen from the meshing together of hundreds of incompatible value systems. Our current governmental models have refused to recognise our rights as human beings, and so it has become necessary for us to rally around a new conception of those rights and to see that it is enforced in the space around us. This sevenfold elemental conception of human rights is the way forward.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 is also available.