Imagine a situation – let’s call it 1970s Sweden – where 99% of the population are Swedish. In such a homogenous society, there is a high level of genetic relatedness. Even people who are not direct family will have a common ancestor a few dozen generations back. Any two Swedes from the same city have an excellent chance of having common family, even if through marriage.

In such an environment, the nation is like an extended family. Any two randomly-chosen Swedes will be some kind of cousin, even if distant. Going back 25 generations – some 500-600 years – means a person will have tens of millions of ancestors. In a country of ten million such as Sweden, that means multiple common ancestors.

Imagine an altruistic action that cost a Swedish person, but which benefitted their society. Putting a shopping trolley away, picking up rubbish, volunteering for community work, donating to charity, choking down rage when someone offends them.

Lets say this person’s pro-social action cost them 100 units of misery, but provided two units of joy to 100 people in their community. If 99 out of 100 members of their community are related to them in some way, that means that 198 units of joy were created for that person’s kin. If everyone in the community contributed in such a manner, then even with a few freeriders it would be possible to have a very high standard of living.

Now imagine a situation – let’s call it 2020s America – where some 50% of the population are of one nation, related by flesh and blood, and where some 50% of the population are from other nations. In such a heterogenous society, flesh and blood relations are not the norm. It’s more common for people to live in neighbourhoods with others who don’t share recent common ancestors.

In an environment like this, society is not like an extended family. Half of the people one meets will be complete strangers – friendly? hostile? no-one has any idea. Any two randomly-chosen Americans have a 50% chance of being part of the same nation, and a 50% chance of being as distant as any two randomly-chosen Earthlings.

Lets say, as in Sweden, that a person’s pro-social action cost them 100 units of misery, but provided two units of joy to 100 people in their community. Because only 50% of the community are kin, that means 100 units of joy were created for the American’s kin from that action. It’s an even equation, and we would expect, therefore, the average American to be somewhat indifferent about such pro-social actions. And they are. This is the main reason why American infrastructure is less well maintained than Swedish.

Now imagine an immigrant whose kin makes up 1% of the local population. It doesn’t matter which country they live in, just as long as their kin are only 1% of the population, and the other 99% are mere strangers.

This person’s pro-social action also costs them 100 units of misery and provides two units of joy to 100 people in the community, just like it does for everyone else. But there’s a difference for the immigrant. Only 1% of the community belong to the immigrant’s kin. So the pro-social action – which costs 100 units of misery just as for anyone else – only provides two units of joy to the immigrant’s kin.

Why not, then, restrict pro-social actions solely to one’s nearest kin?

This is the question that many immigrants end up asking themselves – and the more diverse a society becomes, the more others ask it as well. The inevitable end result is a low trust, dog-eat-dog society.

Imagine now, an action that cost only ten units of misery but produced two units of joy to 100 people in the community. This wouldn’t be a major volunteer effort: it would be more like putting one’s shopping trolley away or putting one’s litter in the bin. Those basic civil behaviours that many Westerners consider normal if they’ve never been to the Third World.

The Swede and the American would both do it without thinking. The payoff for both is obvious. But the logic for the immigrant is different. Ten units of misery might not be much, but 99% of the benefit from making the effort will go to strangers. Only two units of joy will be received by the immigrant’s kin. So it’s still not worth taking the action.

One can see, therefore, that even minor acts of civil respect are no longer performed once the surrounding population is sufficiently different.

These potential actions constitute a basic Prisoner’s Dilemma. Do I cooperate or defect? Co-operating here means to spend time or energy on upkeeping or improving society. Defecting is spending time and energy on one’s closest kin or oneself only.

We can see from basic evolutionary psychology and game theory that people are much more likely to cooperate if doing so would benefit their kin. They know that their kin are much more likely to cooperate in return. This is the basis of altruism. But there’s a flipside: if not enough of one’s kin would benefit from an action being taken, one doesn’t take it.

It’s not as simple as this, of course. People in reality don’t make such hard distinctions between kin and non-kin as in this thought experiment. But however you figure it, there are thresholds of diversity that, once passed, dissuade people from taking various pro-social actions. If the energy from a pro-social action does not help one’s kin but instead just dissipates into the wider world, then why bother? Many people reason this way, and it’s entirely natural.

It’s often asked by social commentators why people don’t contribute anymore. The answer is blackpilling: society has become so diverse that it no longer makes sense to. In diverse societies, people tend to “hunker down”, as described by Robert Putnam in his lecture E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century. Putnam summarises the findings of social psychology research into diversity with “The more ethnically diverse the people we live around, the less we trust them.”

In more specific terms, consider the above logic in terms of support for taxation.

A Swede in 1970 might pay 100,000 Swedish krona in taxes, and not complain, reasoning that his kin will get 99,000 krona in value from it. Even if he assumes that there are no economies of scale from government spending, and that taxation has a redistributionary purpose only, enough of his kin benefit from the redistribution that he can easily reason society is made better thereby.

An American in 2025, by contrast, might pay the equivalent of 100,000 Swedish krona in taxes, and complain heavily, reasoning that his kin will only get 50,000 krona in value. “I can spend my own money better than the Government can,” is a common refrain in America, for this reason. The tax money one pays mostly goes to someone else’s kin. Any economies of scale earned mostly go to someone else.

An immigrant to either society in 2025 might reason that his 100,000 krona only pays back 2,000 krona in value to his kin. Might as well not even bother working if this is the case. Especially if the tax money that pays your welfare is paid by non-kin. Why would anyone feel guilty about being on welfare, if it’s non-kin who have to pay for it?

All this explains why the more diverse a country is, the less taxes people pay. Countries like Sweden, where taxes mostly go to help the kin of the taxpayer, vote for higher taxes than countries like America. Immigrants, for their part, vote for low taxes if a net tax payer and for high taxes if a net tax receiver.

All this also explains the voting patterns of the various American demographics. Highly white, high-trust states like in New England vote for high taxes, just like highly white, high-trust Sweden. White people in multicultural areas like Los Angeles, Houston and Atlanta vote for right-wing parties and for low taxes. Blacks and Hispanics vote for high taxes and more welfare; Asians and Indians vote for low taxes and less welfare. These patterns are to be expected given the game theory of immigration.

As a final thought experiment, flip misery and joy around and think about crimes.

A Swede will be highly disinclined to commit a crime against a random member of his community, because they are probably related. Although many crimes, in practice, are committed against kin, this is almost entirely a function of the proximity effect. In terms of inclination to commit a crime, the vast majority of people are more inclined to attack non-kin, which is the main reason Swedes commit so few crimes.

An American who lives in a community that is 50% kin can be predicted to be only moderately disinclined to crime. Indeed, crime rates are much higher in America than in Sweden. Revealingly, white Americans in 95% white American communities commit crime at a similar rate to white Europeans in 95% white European communities. It’s a different story in the urban jungles of the big cities. There it’s possible to find whites much more violence-prone than the average Swede.

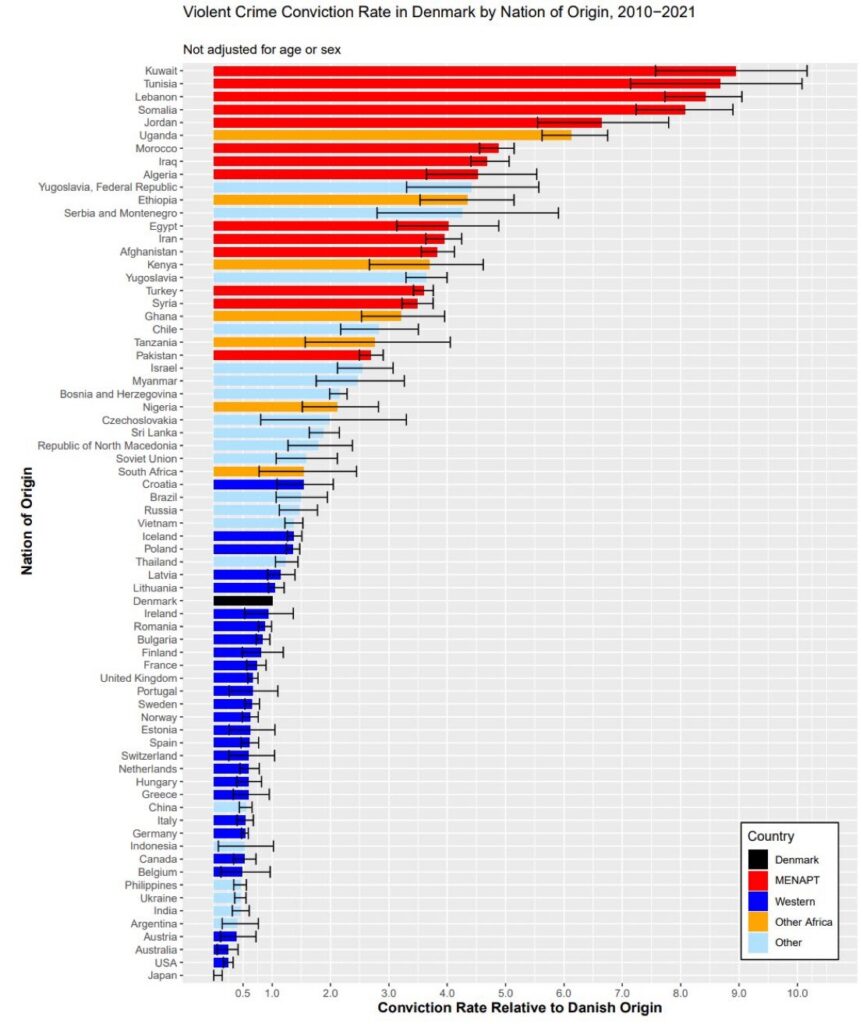

An immigrant who lives in a community that is only 1% kin has very little reason to care about crime. If 99% of people are non-kin, then crime and its consequences are someone else’s problem. Thus you might as well do crime if you feel like it. This is principally the main reason why certain immigrant groups commit such tremendous rates of violent and sexual crimes against the locals. As can be seen in the table above, Kuwaitis commit an incredible amount of violent crimes in Denmark, yet Kuwait itself is not particularly dangerous.

In summary, investigating the game theory of immigration makes it clear that as a society becomes more diverse, ever-more marginal pro-social actions get taken less often, and that society deteriorates. A study in The Quarterly Journal of Economics found that “Trustworthiness declines when partners are of different races or nationalities”. In other words, diversity destroys trust. Because the solidarity inspired by trust is the bedrock of society, it’s no exaggeration to say that diversity destroys society itself.

*

For more of VJM’s ideas, see his work on other platforms!

For even more of VJM’s ideas, buy one of his books!

*

If you enjoyed reading this piece, buy a compilation of our best pieces from previous years!

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2023

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2022

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2021

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2020

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2019

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018

Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017

*

If you would like to support our work in other ways, make a donation to our Paypal! Even better, buy any one of our books!