The Western World risks falling into confusion. Most of us have lived our lives under the impression that we were free people, at liberty to pursue happiness and to discuss ways of achieving it. As we’re now finding out, we don’t actually have the rights that we thought we had. This essay suggests a way out of the predicament.

New Zealanders have, in recent weeks, been surprised to learn that we don’t actually have the rights to free assembly and free speech. This has been demonstrated by the example of controversial speakers Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux, who were forbidden from using a public hall by Auckland Mayor Phil Goff. Stating that he doesn’t believe that the political opinions of the two should be permitted to be spoken, Goff banned them from using the Auckland Town Hall.

Southern and Molyneux, whose talks frequently criticise the suicidal policy of mass immigration, have come in for a savaging from the banker-owned New Zealand media. Because the banks are the ones that profit the most from the bloated house prices and rents that come with opening the borders, they are the biggest cheerleaders for it. Consequently, their peons in the New Zealand media whipped up a mob which threatened violence to get the speakers banned.

This imbroglio has raised an important question: what are we actually allowed to talk about?

One potential solution lies in Peter Dunne’s Psychoactive Substances Act. The logic behind introducing this piece of legislation was that synthetic drug manufacturers were coming up with novel, dangerous substances so quickly that the authorities were unable to ban them all fast enough to keep the public safe. So instead of banning specific drugs that were known to cause harm, the Act simply bans all psychoactive substances.

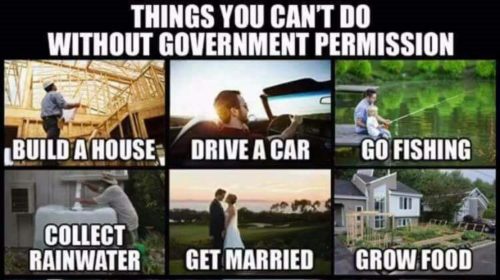

This was a breakthrough in jurisprudence. Anyone wishing to use any psychoactive substance, no matter what it is, even if they just invented it themselves, is automatically a criminal unless they have Government permission to use that substance specifically. An entire class of actions are thereby criminalised, without any proof that actions within this class are harmful to people. They could even be helpful, but they’re still criminal.

We could apply this same logic to free speech and assembly. New ideas come and go in an ever-mutating memescape, and the Government can’t keep up with all the new ideas and opinions that people have and which might be dangerous. The spread of the Internet means that New Zealanders are frequently exposed to opinions that have been formed overseas and brought into the country by way of underground networks, such as 4chan. These new opinions have not had time to be dissected and discussed.

Why not simply ban them all?

The Government could pass a law that bans expression of all political ideas and opinions apart from those that are on a pre-approved list. This list would contain all of the speech that the Government believes is not harmful to anyone else. It could be called the Dangerous Opinions Act. It would then become illegal to express any political opinion that didn’t have an exemption under the Act.

Because talking about the effects of mass immigration on European society risks stirring up ethnic tensions and hatreds, we could simply ban all such talk in advance, thereby precluding anyone like Southern and Molyneux from ever speaking. Discussing racial differences in IQ would then be illegal. Questioning the mainstream media would be illegal. Questioning the Government would be illegal.

Perhaps the Government could create some kind of central authority that can be tasked with determining what opinions may be freely expressed and what opinions have to be criminalised and repressed for the greater good. This Ministry would be concerned with the truth and the promulgation of same, so naturally it should be called the Ministry of Truth.

All of this might sound fairly draconian, but the people would still have the right to petition the Government to allow certain opinions to be expressed. If enough people wanted to express a certain opinion, they would merely need to petition the current Minister of Truth, and perhaps get enough signatures for a referendum on that opinion. Over time, good opinions would become legal while the bad ones stayed illegal.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).