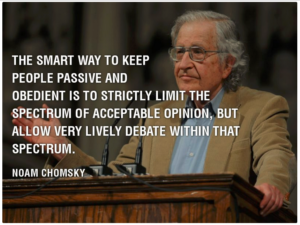

Noam Chomsky said something very intelligent once, quoted in the above image. It’s an extremely perceptive insight because it lays bare at a stroke one of the most powerful tools of deception that the Hate Machine has to levy against you.

The corporate media is very skilled at creating the impression that the war between truth-tellers is a war between TV1 and TV3, or between Stuff and Newshub.

In reality, it is a war between those who seek to force you into that claustrophobic little paradigm of thought that Chomsky referenced, and the rest of us.

An insight into how this works can be gleaned from observation of the incestuous nature of the mainstream media. On Stuff, for example, many of the articles are simply puff pieces that reference other mainstream sources of media, in particular television, the pleb’s choice of medium.

This probably isn’t surprising once you consider that the majority of the New Zealand media is owned by a small number of foreign billionaires. If you own both a television station and a newspaper, then why not direct your newspaper to write about the shows on your television station?

This collaboration is in principle little different to how the major bookstores work in concert to act as gatekeepers for any book or publisher whose message does not serve corporate interests (which is why you don’t find David Icke and VJM Publishing books in Whitcoulls or Paper Plus).

They will say it’s a matter of economy of scale but this dodges the point, because there will always be more money in pandering to the lowest common denominator, which has been true for a long time.

This newspaper warned at the time that the flag referendum was a deliberate waste of time and energy intended to distract us from making progress on real social issues. Predictably, this warning was not heeded by the masses, who indeed wasted many months of time and energy deciding which flag would ultimately be rejected in favour of the status quo.

The accuracy of Chomsky’s headline quote is very evident if one studies the message of the New Zealand media during that period. They presented a meaningless choice between a range of already doomed options, and then simply refused to discuss anything else.

And then, a few months later, they simply did it all again: excluding all political debate of any national significance so that John Key’s hubristic charade could be front and centre.

The end price of $26,000,000 was a win-win-win for the National party: they successfully hamstrung any meaningful debate about the state of society for months, and they made us pay for it, while at the same time cutting access and funding to social services.

The real media war is between those who want to inform you (out of solidarity) and who want to confuse, frighten, mislead and befuddle you (usually out of a profit motive). So if you have a piece of information that is of more value than the average mainstream media puff piece about Max Key or Kate Middleton, then share it.