Paranoid Personality Disorder (PPD) is a condition characterised by extreme distrust and suspicion of other people and their motives. Characters with PPD are well-suited to serving fictional roles as fiendish adversaries or challenging social obstacles. This article gives some useful tips for writing a believable and engaging character with Paranoid Personality Disorder.

People with PPD are generally very low on the agreeableness scale. Characteristic of the condition is an extreme suspicion of other people’s motives. To be paranoid is to be distrusting, and without a significant element of mutual trust it’s impossible to have any kind of social organisation.

A diagnosis of PPD comes when paranoia has led to a level of disruption that has caused significant disruption in the life of that person or others. It’s not hard to see how this can easily happen in the case of extreme paranoia, for the aforementioned social reasons. A person with PPD is unlikely to trust their employer or supplier to not be ripping them off, and nor are they likely to trust a professor or a doctor.

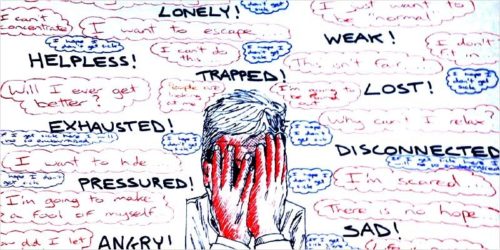

A protagonist with PPD might live in a world of perceived malevolence. They might see schemes, tricks and traps around every corner. No-one ever approaches them with good news, or with a good offer: all human contact represents merely just another attempt to cheat them. In this regard, the life of a character with PPD might be socially impoverished in a similar fashion to someone suffering from Schizoid Personality Disorder, only with distrust replacing indifference.

If the protagonist of your story encounters another character with PPD, chances are high that they won’t like them very much. It isn’t a pleasant experience to be spoken to as if one is a liar, especially when one had never considered actually lying. It also becomes quickly apparent that investing time and emotional energy in a friendship with a paranoid person is unlikely to be reciprocated, because their constant suspicion will quickly lead to them discounting the value of any favours or friendship offered.

This could make for an interesting story if the protagonist was tasked with winning the trust of a character with PPD. Such a story might mean that the protagonist has to find a way to tease out the few remaining trusting elements in that person and making sure that they get rewarded.

It might also mean that your protagonist ends up learning exactly how someone can end up with PPD in the first place. Perhaps the character they are interacting with did genuinely get cheated, on multiple occasions, by liars who they once trusted: parents, teachers, lovers, bosses. There could be a further twist, if the character with PPD brought all this upon themselves owing to their own malignant personality.

It’s common for individuals with PPD to have what appears to be a “fragile” personality. Ambiguous comments are frequently interpreted as personal attacks, and jokes are often taken in bad humour. Even worse, these reactions are often permanent, because individuals with PPD do not readily forgive slights and insults. For obvious reasons, such behaviour tends to attract enemies, which only serves to fuel the paranoia and mistrust.

A commonly related phenomenon to PPD is that of projection. People who are paranoid are often narcissistic in the sense that they think everything is about them. For this reason, they tend to project their own selfishness and malevolence onto other people. Many cases of paranoia are based on the fact that the paranoid person is themselves not worth trusting.

Some theorists have delineated a variety of subtypes of PPD. Some people with it are particularly stubborn, obsessed with order and regularity and consumed by a fear that someone is trying to cheat them out of something. Others are insular, and lead hermit-like lives far away from the crowds of crooks and criminals that make up society. A third type is malignant – their distrust of other people comes from from suspicion but from hatred.

It’s unlikely that a character in your story will see it as a good thing to encounter a person with PPD, but it is possible. After all, paranoia is an extremely useful aptitude in a variety of security and surveillance-related roles. So if you’re writing about a spy, for example, you might use touches of PPD to flesh out their personality. A character who was once an intelligence officer, but who was let go because they became too paranoid, would be a fitting example.

An interesting twist on a story featuring a character with PPD is if they were actually correct. What if the PPD character was correct in their suspicions of everyone else, and there was, in fact, a great conspiracy or scheme going on?

An important distinction to make is the one between PPD and paranoid schizophrenia (note that paranoid schizophrenia is not in the DSM-V). Paranoid people don’t hallucinate from paranoia alone, and the paranoia involved in PPD is not ludicrously delusional. In other words, a person with PPD may have a twisted conception of reality, but they will not have lost touch with it.

*

This article is an excerpt from Writing With The DSM (Writing With Psychology Book 5), edited by Vince McLeod and due for release by VJM Publishing in the summer of 2018/19.