Depersonalisation Disorder is a brutally surreal experience. Also known as Derealisation Disorder, this condition is characterised by feeling like an outside observer of one’s own body despite being in it, and feeling like one isn’t actually in control of that body’s actions. Also common are feelings about reality being vague, dream-like, or less real than usual. This article gives some hints for how writers can handle characters with Depersonalisation Disorder.

This condition is almost always the result of stress, but a distinction needs to be made between a person who is temporarily dissociating in the moment because of an intensely traumatic event that has just happened, a person who has an established pattern of dissociating when exposed to certain stimuli that should not themselves be distressing, and a person who has a tendency to dissociate under small amounts of stress owing to psychological damage from past trauma.

It has to be made clear that Depersonalisation Disorder is not the same thing as psychosis. A person in a dissociated state will be aware that their perceptions are altered (or, at the very least, that something is wrong). In other words, they will not have lost touch with reality, which is a necessary quality of a psychotic experience. They will just have dissociation.

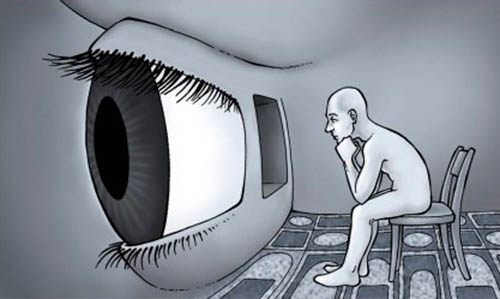

Dissociation is when one starts to feel emotions and sensations that aren’t usually associated with the environment that one is in. For example, one might be in an extremely stressful situation but not actually feel any stress: one simply watches everything from the perspective of consciousness, as if floating outside the body. Things feel unreal, surreal, so that sometimes one feels as if one is watching a film with one’s life on it instead of actually living it.

This lack of connection with the body is the strangest and most difficult thing about the condition. A person with depersonalisation can look at their own hand and not feel like they’re looking at their own body, which is a highly disconcerting experience. It’s also disconcerting to look at yourself in the mirror and not really understand who it is or that it’s you, or to recall a past memory and feel as if it really happened to someone else.

If written from a first person perspective, and written well, the experience of a character with Depersonalisation Disorder might be terrifying to the reader. Dissociation is often terrifying to experience personally, especially for the first time, and may be difficult to distinguish from a panic attack. However, often it is more weird than frightening, especially when the alternative is genuine suffering.

If the dissociation is occurring in a character being observed by the protagonist, that character might seem distant, vacant and “spaced-out”. The protagonist might get emotionless, zombie-like responses from the character undergoing dissociation, which might be a problem if there is something that has to be done quickly. It’s very possible that the protagonist mistakes the person dissociating for being under the influence of a psychoactive substance.

Most readers don’t do a lot of drugs. If they do, they might find the experience amusing to read about. After all, dissociation is a common effect of many recreational drugs. For such an audience, a character’s bout of dissociation might come across as highly comical, and doubly so when paired with another character who is perfectly straight in all regards.

Like most psychiatric conditions, Depersonalisation Disorder is believed to have an origin in psychological trauma. It’s very possible that a character with the condition will have experienced repeated trauma in childhood (usually emotional) that was so relentless it caused the mind to dissociate with reality in order to protect itself. This could be abuse, or a witnessed tragedy, or even simply a realisation about the true nature of things.

The case of Depersonalisation Disorder might then be an ego protection response to extreme trauma so that the person suffering the trauma doesn’t become cruel as a consequence of the suffering. Essentially one goes mad, when under inhumane stresses, in preference to becoming evil. This might be a way of showing the inherent goodness of a character, or their inherent naivety, depending on one’s approach.

Writing about a character who has dissociation might not be very interesting if the story revolves around the dissociation itself. The story might be more interesting if your character is an otherwise mentally healthy person who becomes dissociated as a result of extreme circumstances. This might be a one-time event or it could be part of a pattern.

If it’s a one-time event, it might be a reaction to a grisly sight like a car accident or something seen on a battlefield. This need not, then, be the central role in the story, but might rather be something that befalls the protagonist at a particular juncture, possibly transforming them or causing them to grow.

If part of a pattern, it might play a more central role in the story. It may be that the sight of a certain thing triggers an episode of dissociation on account of being associated with what caused the initial trauma, or it could be that relatively small amounts of stress or uncertainty are enough to tip a character over the edge.

*

This article is an excerpt from Writing With The DSM (Writing With Psychology Book 5), edited by Vince McLeod and due for release by VJM Publishing in the summer of 2018/19.