This reading carries on from here.

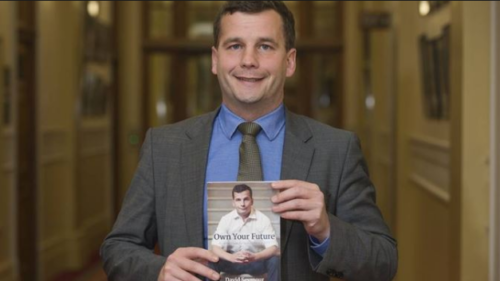

The second chapter of Own Your Future is titled ‘Tax’. Seymour opens with a complaint about wasteful government spending, citing the example of Gerry Brownlee flying to San Francisco on the taypayer’s dollar for a photo op. Indeed this was an appalling waste of money for no benefit to the nation, but Seymour leaps from this fact to the tacit assumption that all tax money is likewise wasted.

Seymour is right when he says it’s stupid that the Government is running surpluses while the average New Zealand household is at record levels of debt. The solution is, naturally, lower taxes. Here Seymour makes a sharp distinction between “our own” money, and “another person’s” money. Not for him the interdependence of all things. In Seymour’s world, there are very clear lines over who owns what.

Government takes in taxes equal to 40% of GDP, Seymour notes – “exclusively” another person’s money. Seymour doesn’t agree with the idea that the state is the most efficient provider of many services on account of the economies of scale afforded by its unique size. For him, the Government is merely a parasitic entity that sucks tax money out of hard-working Kiwis and wastes it frivolously.

Breaking step with the usual neoliberal choice of target, Seymour points out that there is a tremendous amount of corporate welfare in New Zealand as well. This only lasts for a few sentences, because he’s soon back to crying about taxation. Bracket creep comes in for particular ire – for Seymour, the wealthy aren’t getting a big enough share of the spoils of economic growth.

True to being a politician, he is dishonest. He claims that bracket creep happens because wages rise (which is true) but he also claims that wages rise to meet the increase in the price of consumer goods. The truth is that wages are not linked to the inflation of consumer goods – they are a function of the relative leverage that the employer has over the employee. When consumer goods become more expensive, this gives the employee absolutely no additional leverage through which they can negotiate a higher wage with their employer. If anything, it gives them less leverage because the lower standard of living makes them more desperate to settle.

In one paragraph, Seymour abandons even the pretense of reasoning and simply lists American libertarian slogans: “High tax rates… drag the economy down”, “people spend their money better than governments do”, “Money goes more good in the private sector than in the public sector.” Again one senses the cold shadow of the millions starved to death by Communism.

Seymour makes some good and fair points when he talks about the bureaucratic waste in the system. The problem is that this waste is the only thing he sees – all Government spending is hip-hop tours and junkets to San Francisco. He will not acknowledge that tax money is used for anything good, or that taxpayers get anything back for their tax money. National are the good guys because they levy less tax; Labour are bad and the Greens are the worst of all.

It’s hard to disagree, however, when he complains about the top tax bracket being $70,000. One doesn’t have to be wealthy to concede that someone earning $70,000 a year is far from loaded.

In all, one feels that Seymour is capable of making some good points but has a dishonest method for selecting and presenting them to the reader. Despite that, it’s easily arguable that Seymour and his party are tasked with playing an important role in New Zealand politics – that of keeping a check on Government waste – even though they are apologists for neoliberalism.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).