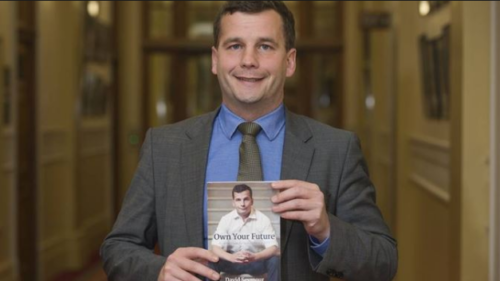

Today, VJMP Reads has a look at Own Your Future, by ACT Party Leader David Seymour. This is a 192-page book of essays published by the ACT Party along the lines of previous ACT Party efforts such as Closing the Gaps and I’ve Been Thinking.

Previous VJM Publishing publications, such as Dan McGlashan’s Understanding New Zealand, tells us some basic facts about the ACT-voting demographic. Although few in number (a mere 13,075 in 2017), they were the wealthiest voter base of any party, as well as the most likely to be born overseas and one of the best educated (along with the Greens). Asians like them the most, white people the next most, and Maoris the least.

We have also seen that people who donate to the ACT Party get the worst return on their investment, with the party gaining 22 votes per $1,000 spent on the 2017 campaign. This compares to 388 votes per $1,000 for Labour, 452 for National and 4,761 for the Aotearoa Legalise Cannabis Party (even the vanity project that was The Opportunities Party managed 62 votes per $1,000 spent).

So who are ACT, in the words of their own leader?

The Introduction runs to sixteen pages, and is worth studying on its own. It starts off by telling the story of the struggles of a wealthy couple to subdivide their land. Hilariously, by the third page there’s already a reference to how, under communism, “people starved by the million”, so it’s already a fair bet at this early stage that the book will be full of far-right-wing American-style libertarianism.

On page 12, Seymour states that he grew up “not rich”, and also states that the first time he realised that the Government might not have our best interests at heart was at age sixteen. Seymour was born in 1983, which would make him around 8 years old at the time of Ruth Richardson’s infamous 1991 Budget, which ripped the heart out of the New Zealand poor. Had it not occurred to him in the aftermath of the social destruction wrought by this that the Government is not on the people’s side, then it can fairly be said that he was unusually privileged, if not actually sheltered.

In fact, the truly sheltered nature of Seymour’s life comes through in lines that would be comic genius in any other context. How else to read “Auckland Grammar is a particularly barbaric place for some kids. I vividly remember one kid getting a tennis ball to the head, it bounced lightly but its power was symbolic”?

Like most men of his time, Seymour is a materialist. He is proud to have supported liberalising the abortion laws. ACT wanted to introduce laws that would make New Zealand a better place, in Seymour’s estimation, hence his support for them. This is stated very matter-of-factly, with no explanation as to why he thought that ACT in particular were best suited to make New Zealand a better place.

Inevitably, Seymour has a go here at the eternal ACT bugbear, the Resource Management Act. He writes that the poorest fifth of New Zealanders spend almost half of their income on housing today, compared to only a quarter of their income 26 years ago. All of the blame for this can be laid at the feet of the RMA, which has strangled the rate of house building. “That’s why people are living in cars and garages.”

The obvious rejoinder to this claim is to point out that New Zealand has the highest rate of immigration of any OECD country. Seymour anticipates this, and writes of the immigration question that opinion is divided between “National’s naivete vs. the racism of New Zealand First.” Like many middle-class white people, Seymour appears to be unaware that New Zealand First’s strongest supporters are Maoris.

Seymour generally doesn’t seem bothered by anti-Maori racism, as shown by his rant about “million after million for various Maori centric projects and separatist legislation”. Racism is, perhaps, only real to Seymour when it prevents wealthy foreigners from immigrating here (after all, as noted above, Maoris don’t vote for the ACT Party).

Going by the introduction, this book seems like the closest thing to a neoliberalist manifesto New Zealand has seen recently. What Seymour appears to be about, fittingly for someone who represents foreign wealth, is freedom for money. He’s not interested in freedom for people. Freedom for people comes incidentally, in so far as those people have money.

One gets the impression that if Seymour could stuff the entire South Island into a giant machine that sorted it out into its constituent minerals for the sake of most efficiently selling it all off to foreign speculators, he would be happy to do so. This book, therefore, promises to be a journey into the mind of an absolutely fanatical die-hard neoliberal.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).