A common argument for cannabis prohibition asserts that cannabis is a gateway drug, in that using it inevitably leads people to using harder and harder drugs. The idea is that we need to keep cannabis illegal so as to keep people off the pathway that leads people onto truly destructive substances. As this article will examine, there is a modicum of truth to the gateway effect, but not in the way it’s usually presented.

The usual way that the gateway drug theory is portrayed is as follows. An individual tries cannabis for the first time, and experiences a cannabis high. This is a pleasurable sense of peace and euphoria that the user decides they want to have again. So they try cannabis again, and have a good time again. So they use it some more, and soon find that they need more and more of it to get the same level of hit.

Eventually the user is addicted to cannabis. After a while, cannabis is no longer able to do the job. At this point the drug user naturally comes to seek out harder drugs, such as methamphetamine, cocaine and heroin, in the hope of getting a chance to relive the original amazing high that cannabis gave them. For some reason, the idea that cannabis use leads to heroin use is particularly prevalent in some circles, especially among the elderly (which reveals that the genesis of the gateway drug theory is in old-fashioned superstition).

The logic is that cannabis prohibition should prevent people from getting exposed to that initial cannabis high, by way of making the substance harder to get hold of. The harder it is to get hold of, the fewer people get addicted, and so the fewer people who seek out really hard and destructive drugs. Therefore, cannabis prohibition protects people from the harmful effects of, for example, methamphetamine or heroin addiction.

The reality is that the gateway effect is a phenomenon that is caused entirely by cannabis prohibition, and which would mostly disappear if there was cannabis law reform, except for in the case of people who have a deathwish.

Many drugs are illegal. Of those, cannabis is particularly badly suited to serving as a contraband substance. It has a strong smell, is bulky and doesn’t generate much raw profit if one considers how much time and expense goes into cultivating, transporting and storing it. Most other contraband substances are much easier to deal with and more profitable, especially those of the powdery kind.

For this reason, many unscrupulous cannabis dealers use cannabis as a kind of lure, by which customers can be induced to buy more profitable (and/or addictive) substances. It’s common in New Zealand for cannabis dealers to suddenly “run out” of cannabis when a particular customer comes around, only to offer a hit of methamphetamine by way of compensation. If the customer decides that they do like it (and this is very common), the dealer is right there to sell them a point bag.

When the would-be cannabis user is then hooked on methamphetamine, they are much more profitable than they would have been if the only other option was to sell them an ounce of weed every two weeks or so. A person who is into methamphetamine is able to burn through thousands of dollars in a week. A dealer can potentially make twenty times as much money selling methamphetamine to a person than they could selling cannabis.

So the idea that cannabis is a gateway drug is untrue. There is such a thing as the gateway effect, but this only exists because of prohibition, in particular because of the opportunity that prohibition creates for drug dealers to get naive cannabis-seeking customers hooked on harder drugs. Far from being a gateway drug which leads to people recklessly doing coke, crack, meth, smack and anything else they can find in search of a buzz, cannabis has shown promise as an exit drug for conditions like heroin addiction and even alcoholism.

If cannabis was legal, people who want to use it could simply go to a cannabis cafe or cannabis store, buy their sativa or indica as desired, and then go home without being exposed to methamphetamine or heroin or anything else. A clerk at a cannabis store is no more likely to offer the customers methamphetamine than a bartender would. After all, they already have a steady and secure income through selling a legal drug to a set market, so why would they want to screw that up?

The truth is that cannabis prohibition forces people into the arms of criminals. This is the true causal origin of the gateway effect. Repealing cannabis prohibition would mean that the people who want to buy cannabis don’t need to encounter criminals in order to so, and consequently never get exposed to a dealer offering to sell them a truly destructive drug.

*

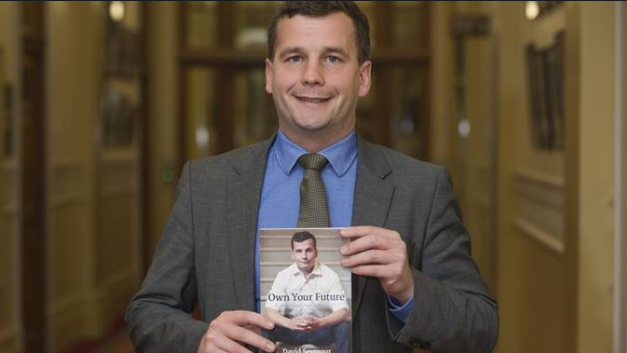

This article is an excerpt from The Case For Cannabis Law Reform, compiled by Vince McLeod and due for release by VJM Publishing in the summer of 2018/19.