The perennial philosophy comes and goes, all throughout time and space, being a reflection of the mind of God in the Great Fractal. In every new age it updates itself, taking a form that makes sense to the people of the time, depending on the characteristics of that age. Because technological change has been so rapid over the last 150 years, the perennial philosophy has not been able to keep up. This essay makes an attempt to do so.

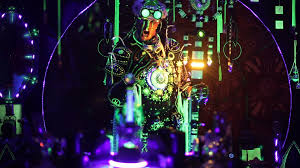

The metaphors of the former age were the crucifix, the fish and the crescent, just as they were the pyramid, the bull and the sacrificial brazier in the age before that. The age that we are now entering has its own zeitgeist – perhaps it is time for a technoshamanic update to the perennial philosophy?

The perennial philosophy is informational gold and is more fundamental than language and therefore cannot be described in words. However, we can predict what some of its teachings are going to be, by applying the axiom of “As below, so above” to the modern day.

In its earlier incarnations, through the writings of Hermes Trismegistus and others, the perennial philosophy explained the metaphysical world by analogy to the natural world. “That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above, working the miracles of one,” reads the Emerald Tablet, “Its father is the Sun and its mother the Moon.”

This remained an extremely effective metaphor, until today. The world of today is so bizarre, so surreal and impossible that distinguishing it from a dreamscape is no longer easy. Moreover, modern people are almost completely out of touch with the natural world – many of us haven’t so much as looked at the Moon in years.

We need a new metaphor for a new age, and virtual reality seems like the obvious replacement.

Following this line of reasoning, one might expect that the creation myths of the new century will be based around the same binary division as always but with a modern twist; in other words not of yang and yin, fire and water or Sun and Moon but of 1 and 0. The hardware is the brain, the software is the mind, and electricity is the Holy Ghost.

Different lives could be seen as nothing more than differing sets of sensory impressions upon consciousness. As long as these impressions could be accurately recorded and reproduced, there’s no reason why they couldn’t be accessible for any conscious person to experience at any time.

My own The Verity Key twisted the ordinary perception of consciousness through a machine that could replace the consciousness of another person with that of the operator of the eponymous device. The idea was to play on the usual belief of the reader that their consciousness was directly connected to their physical body, and could never be separated.

This played with the idea of the Great Fractal, which is conceptualised as an immense algorithm that calculates all of the possible combinations of senses that make up the illusion of the material world. This is a modern way of expressing how all things flow from one, i.e. “all created objects come from one thing, an undifferentiated primal matter”.

In other words, all of the contents of consciousness ultimately flow from consciousness itself, because nothing more than consciousness is needed to create them all – a fact known to all who have managed to purify their consciousness to the level of gold and thereby completed the Philosopher’s Stone.

Other ancient alchemical or hermetic beliefs can likewise be transliterated into a modern context.

The laws of karma can be expressed in terms of frequency, which no-one understood before the days of widespread radio, and which now everyone does. If one can imagine such a thing as a frequency of consciousness, a higher frequency would produce a more harmonious tone and joy among those who heard it, whereas a lower frequency would produce a discordant tone and fear among those who heard it.

A technoshaman might contend that, upon the expiration of one’s physical body, the frequency of consciousness that one had cultivated is the only thing that passes into the next world. They might even go as far as to contend that this frequency will attract those of a like frequency, and therefore that, post-death, one’s frequency dictates which part of the Great Fractal one’s consciousness becomes attuned to and the frequency of those who populate it (until, of course, one dies there as well).

One’s “frequency of consciousness” can here be likened to an analog television or radio signal. The more pleasurable frequencies are not necessarily the first ones discovered, or the most popular ones, and they certainly aren’t the easiest to tune into. In order to tune into higher frequencies one must know where to find them on the dial.

The alchemical quest of transforming lead into gold is a physicalist metaphor for the mystical quest that, in modern language, could be said to be about tuning a low frequency of consciousness into a higher one.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).