Dan McGlashan’s Understanding New Zealand is currently undergoing final preparations for publication and release. This means that the most comprehensive demographic survey of New Zealand ever conducted is about to be available to Kiwi readers in paperback form!

As a sample of what is in the full version of Understanding New Zealand, this article looks at the ten strongest positive correlations in this study, out of all 9,870 of them.

10. Working in professional, scientific and technical services and having an income between $100 and $150K had a correlation of 0.918. This is not very surprising at all, because it is well known that working in any of those occupations requires a very high level of knowledge and skill and that is usually well compensated.

9. Working in financial and insurance services and working in professional, scientific and technical services had a correlation of 0.920. Obviously a person can’t work in both, but the reason for this strong correlation is that both industries are almost exclusively confined to the central city electorates of Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington.

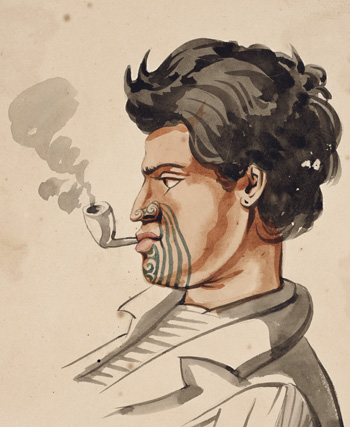

8. Being Maori and being a regular tobacco smoker had a correlation of 0.922. This is an astonishingly strong correlation if one considers that there is no known racial inclination to smoke tobacco.

The reason for it is probably because people generally need to be doing it quite hard to smoke tobacco, because its medicinal effects are outweighed by the physical damage unless a person is under severe emotional distress.

For these reasons, because the majority of the people who are doing it the hardest are Maoris, it’s also the case the majority of Kiwis who are currently regular tobacco smokers are Maoris.

7. Being a Hindu and being a Muslim had a correlation of 0.929. Like point 9 of this list, the two categories are mutually exclusive, and therefore the correlation represents the high physical proximity that the two groups live in.

The explanation for it is that both Hindus and Muslims are part of the most recent waves of immigrants, and so the vast majority of both groups live in the same neighbourhoods, in particular poor ones in Auckland.

6. The correlation between voting ACT in 2014 and being born in North East Asia was 0.937. This might seem like a very strange statistic until one considers that much of a person’s voting preference is a function of two factors – their degree of solidarity with other Kiwis and how much that solidarity will personally cost them.

Anyone not born in New Zealand will necessarily have the least amount of solidarity with other Kiwis on account of having the least in common in terms of heritage and culture, and those born in North East Asia are usually earning an income at or above the Kiwi average – and so pay more taxes.

Thus it can be seen that the ACT Party, in that it most unashamedly considers money more valuable than people, attracts the bulk of these voters.

5. The correlation between being Congregational or Reformed and being born in the Pacific Islands was 0.943. This is because this group reflects a religious tradition that is extremely popular in all of the Pacific Islands apart from New Zealand.

4. The correlation between being Buddhist and being Asian was 0.950. Some might find this surprising because they know a lot of non-Asian Kiwis who are “really into Buddhism”.

Few of these people, however, would go as far as identifying with Buddhism when they fill out the census forms – unlike Asians born in Thailand and in other countries where Buddhism is mainstream, of whom there are tens of thousands in New Zealand.

2=. The second strongest positive correlation was between voting National in 2014 and voting to change the flag – this was 0.954. As Section 56 of Understanding New Zealand discusses in detail, the entire flag referendum project was essentially a National Party vehicle.

2=. Equal with this was the correlation between being a Pacific Islander and being born in the Pacific Islands. A correlation of 0.954 here tells us that, not only are the bulk of Pacific Islanders in New Zealand not born here, but that they tend to choose to live in geographical areas full of other Pacific Islanders (in particular South Auckland).

Although many Kiwis of Pacific Island descent are born in New Zealand, many of these have moved out of Auckland and therefore away from the bulk of those born in the Pacific Islands. These two factors explain this extremely strong correlation.

1. The strongest positive correlation in all of New Zealand was that between voters in the first flag referendum and voters in the second flag referendum – this was a whopping 0.985.

This combines the fact that the entire project was a National Party vehicle with the fact that those who like to vote tend to take every opportunity they can to do so.

*

This article is an excerpt from Understanding New Zealand, by Dan McGlashan, published by VJM Publishing in the winter of 2017.