If the Spear of Destiny ever comes to New Zealand, we ought to be ready to receive it. To that end, we can act to attract it, by employing the Law of Attraction. We can do that by promoting a cultural movement that recognised the excellence of New Zealand and our future greatness. This essay describes a mystical tradition that could serve these ends: Esoteric Aotearoanism.

Elementary alchemy has it that if one combines masculine and feminine in the right manner, one achieves a combination that is greater than the mere sum of its parts. By combining the feminine clay and the masculine iron, it’s possible to get silver, an element neither feminine nor masculine but somehow both, and not just both but the correct proportion of both.

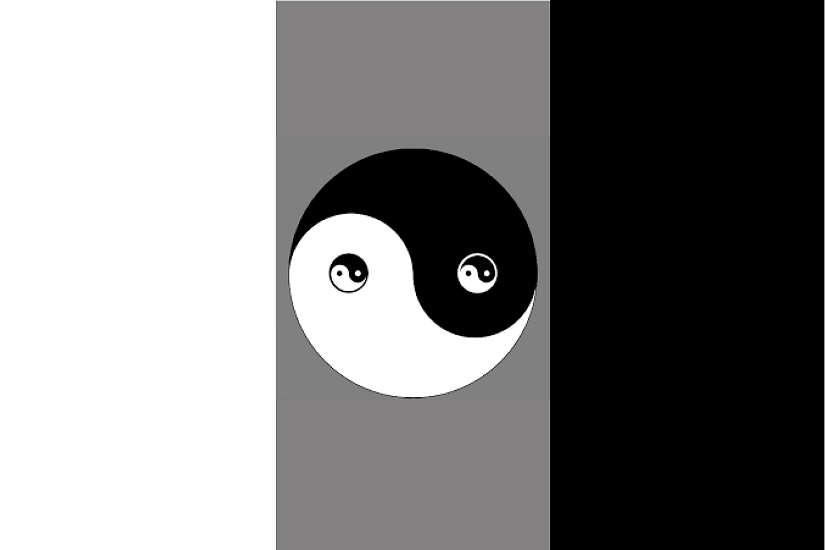

This is represented in Taoism by the Taijitu, which combines the white yang and the black yin to create a shape that has a life of its own, one that tells a story. The energy, light and life of the yang projects itself into the darkness of the yin, which in turn follows the yang in devotion. The result is a spiral that turns for eternity.

Esoteric Aotearoanism tells a similar story. This story is represented in the flag of Esoteric Aotearoanism, which consists of three vertical stripes: the leftmost white, the rightmost black, and the central one silver. It is crucial to note here that the central band is silver, and not grey, because the combination of the two parts has created something more valuable than their mere summation.

The opening degree of Esoteric Aotearoanism is that the Esoteric Aotearoan flag represents the nation of New Zealand in the Kiwi people.

The white is yang, which represents the British. This is not just because the British are white, but also because they are orderly. The British came from the West and therefore the leftmost third of the flag is white. It is from there that the energy and organisation to create the institutions of New Zealand came.

The black is yin, which represents the Maoris. As with the British, this does not simply reflect skin colour, but rather a vital, invigorating passion. Because the Maoris come from the East, the black occupies the rightmost third of the flag. It is from there that the soul of the nation comes, and how we get direction to differentiate ourselves from the globohomo masses (and from Australia in particular).

The silver stripe represents New Zealand, the space where those two ingredients meet, and where they combine to become something more valuable than either. The yang is bright but unyielding; the yin is gentle but dull. Together they are colourful, and shine as silver. As silver is more valuable than either iron or clay, so too is the combination of British and Maori more valuable than either alone.

The silver stripe also represents those who have come together under the silver fern, because they have acted to create something that is greater than either the British or the Maori components. It signifies that what we have of greatest value is that which comes from the land here. It’s not what we imported from Britain or from Polynesia – it’s what we have created ourselves here, according to the direction of our own wills and of the spirit of the nation.

It’s also a reminder that our future lies in the unity of these two forces.

Sir Apirana Ngata hinted at Esoteric Aoteraroanism being the way forward when he said:

Ko to ringa ki ngā rakau a te Pākehā

Ko to ngakau ki nga taonga a o tipuna Māori

Ko tō wairua ki to Atua

In English this means “Your hands to the tools of the Pakeha, your heart to the treasures of your Maori ancestors, your spirit to God.” The sentiment behind this was that we ought to take the best of both worlds. Both the Maori and the European world brought things that were good and things that were bad. We can take the best of both, and leave the worst of both.

This leads naturally into the teaching of the second degree of Esoteric Aotearoanism, in which the various qualities contributed by the British and the Maori are mapped onto the four masculine elements.

The clay represents the Maori. This is because he is vital and passionate, but has a dark side of sometimes expressing unrestrained violence. He is soft and likes to share, but this can sometimes lead to a lack of discipline.

The iron represents the Briton. This is because he is hard and disciplined, but has a dark side of sometimes being cruel. He is orderly but can sometimes be hard-headed, unforgiving and pedantic.

The silver also represents the Briton (this conception of silver is related to, but separate from, the conception of silver in the first degree). This is because his scientific and technological prowess made it possible for New Zealand to become wealthy and prosperous, and for us to defend ourselves without need for submission.

The gold also represents the Maori. Like the clay, the Maori is soft, but he is also colourful. This represents spirituality and an understanding of the world beyond. The Briton is intelligent but he is spiritually ignorant. The realm of gold is where New Zealanders connect to God, and the Maoris, particularly those with an enthusiasm for cannabis or psilocybe wereroa, have a vital role to play here.

Esoteric Aotearoanism considers it a tragedy for a Kiwi to identify as either a white person or a Maori. This would be like denying one of your parents. It’s a small-minded and petty thing to do. That sort of solipsistic narcissism will lead to the nation tearing itself apart down the centre. To identify as one and repudiate the other is an idiocy that is promoted by the enemies of this nation.

In reality, Kiwis are already so intermixed that as many as a quarter of us are some kind of Northern European-Polynesian hybrid. It is this sort of person – not Maoris – that is unique to these isles, the true tangata whenua. There are Europeans in Europe and Polynesians in the Pacific, but only in New Zealand can those who are a mix of the two truly say that they have a home.

This leads onto the third degree of Esoteric Aotearoanism, which deals with the future of the two contributors to Aotearoa. The fact is that white people and Maoris are interbreeding at an extremely high rate, and therefore will eventually mix into one people, who are not separated by category but only by degree. Even then, it will not be a degree of value but simply a degree of proportion of yin or yang.

This people will be a true Kiwi people, and they will best be able to channel the best of the yang and the best of the yin to create something truly precious. Many of them will be among the most excellent individuals on Earth on account of hybrid vigour. There are already plenty of examples of this, such as Buck Shelford, Shane Bond, Michael Jones and (allegedly) Dan Carter.

In all, Esoteric Aotearoanism is a new narrative for a new century, one that repudiates the nation fighting against itself, and one that encourages the nation coming together to embellish the strengths and ameliorate the weaknesses of its constituent parts. This is a narrative that, if supported, can bring peace and prosperity to all Kiwis.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2018 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis). A compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 is also available.