Another Soccer World Cup, another champion from Europe. Everyone is waxing lyrical at the moment about how wonderful the Soccer World Cup is, and how it bring all nations together in harmony with a common goal. The truth, as this essay will demonstrate, is that cricket is more of a global sport than soccer by at least three major measures.

Geographic representation

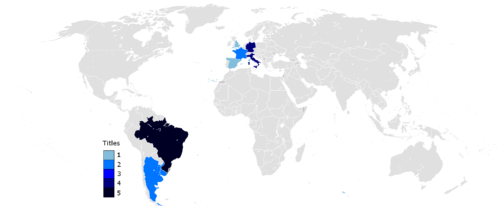

As can be seen by the quarterfinalists of the recently concluded Soccer World Cup, soccer is still very much a European sport. Six of the eight quarterfinalists came from this one continent that contains less than 10% of the world’s population.

Over the last three FIFA World Cups, 23 of the 24 quarterfinalists have come from either Europe or Latin America. The single exception was Ghana, back in 2010. So only two continents are ever really represented by the finalists in Soccer World Cups. Asia, Africa, Anglo America, Australia and Oceania don’t feature – a group of countries that includes the world’s five most populous.

For the most part, only Europeans and South Americans really play soccer, but they are capable of getting an extremely high level of performance out of Africans that have been integrated into European structures. Sufficient evidence for this comes from the fact that France won the 2018 World Cup just now.

Since World War Two, only one team from outside Europe and Latin America has ever made a Soccer World Cup semifinal: South Korea in 2002, and they only advanced that far thanks to some extremely questionable refereeing decisions. Every single other semifinalist has been from one of two continents. This is hardly befitting of “the world sport”.

The Cricket World Cup, by contrast, brings the entire world together. The last Cricket World Cup, in 2015, featured teams from four different continents at the semifinal stage: Asia, Africa, Australia and Oceania. Teams from North America and Europe have previously contested finals, meaning the overall reach of the sport is greater than that of soccer.

Population

Some people object to the statement made in the first section of this essay. Although most are willing to concede that the geographical representation of soccer is not great, many will nevertheless insist that Europe is a great population centre and therefore can’t merely be counted as one continent. This may have been true a century ago, but no longer is.

The population of Europe is 741,000,000. The population of Latin America is 640,000,000. This means that virtually all of the Soccer World Cup quarterfinalists throughout history come from a bloc of 1,381,000,000 people, roughly 20% of the world’s population.

The remaining 80% of the world’s population – comprising China, India, Africa, Indonesia and Pakistan – essentially never get representation among the final eight teams of Soccer World Cups. India and Pakistan have both won Cricket World Cups, by contrast, and are perennial quarterfinalists along with Bangladesh, South Africa and Sri Lanka.

The population of India, where cricket is the only game in town, is 1,325,000,000, essentially the same as the combined populations of Europe and Latin America. This is a fact that needs repeating for those who think that soccer is the global game: the combined populations of the only places capable of competing at the top level of soccer only just equals the population of India alone.

Measuring population properly requires that we add, to the cricket-fanatic side of the ledger, Pakistan (pop. 208,000,000), Bangladesh (pop. 163,000,000), Sri Lanka and Australia (c. 60,000,000), plus several million others in England, South Africa, New Zealand, Ireland and the West Indies, where cricket might not be the national sport but is still one of the major ones.

Against this, soccer has much less overall market share in the countries in which it is popular than cricket does. In Europe and Latin America, soccer has to compete with volleyball, basketball, tennis, handball and golf; in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, cricket is completely dominant. Therefore, it must have more total fans in the world than soccer does.

Appeal within nations

Possibly the most crucial of the three difference between the sports is this one. Soccer mostly appeals to a lower socioeconomic demographic, for who the sport is an escape from the drudgery of everyday life, akin to a circus. Cricket, by contrast, appeals to a higher socioeconomic demographic, for who the sport is the complete test of mental and physical strength and skill and more akin to improvisational theatre.

Soccer players are frequently crude, brutal, thuggish. They cheat so shamelessly that many consider it part of the game. Cricket is a sharp contrast. Men like Rahul Dravid, Ross Taylor and AB de Villiers are complete gentlemen: gracious in victory and defeat, magnanimous, charismatic, serene. Former Indian captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni is literally a prince. He is the upper class of the upper class, an aristocrat by any measure.

If any doubt remains that soccer fans are inherently more base than cricket fans, simply examine the writings of former cricketers like Martin Crowe and Kumar Sangakkara on CricInfo. There is no soccer equivalent.

What soccer is – and this is the cornerstone of its apparent popularity – is the McDonald’s of world sports. It’s a corporatised appeal to the dopamine-deprived brains of society’s lowest common denominator, which is all it can really be on account of its simplistic and luck-based nature. Soccer fans like to tout the ease of understanding the sport as one of its drawcards, but it reality this simply makes it boring to anyone with an IQ over 110 or so.

Over a billion people watched the final of the 2018 FIFA World Cup, according to FIFA themselves. However, more people saw the India vs. Pakistan match during the 2015 Cricket World Cup. The world record for concurrent viewers to a live-streaming platform was set at 10,700,000 earlier this year, not by the final of a European soccer league but by the Indian Premier League of T20 cricket.

What does it mean that more people watch a group match in the Cricket World Cup than the final of the hypefest that is the Soccer World Cup? What does it mean that more people watch the final of an Indian cricket league than the final of any European soccer league? It can only mean that cricket appeals to more human beings than soccer does.

In summary, the delusion that soccer is the “global game”, simply because it’s played in Europe, Latin America and Africa, has to end. Europe is now less than 10% of the world’s population, barely more than half of the population of India alone. If those Indians are to be considered people of equal value to the Europeans, it must be conceded that their passions are of equal value. If so, cricket is a more passionately-followed sport than soccer, measured on a global basis.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).