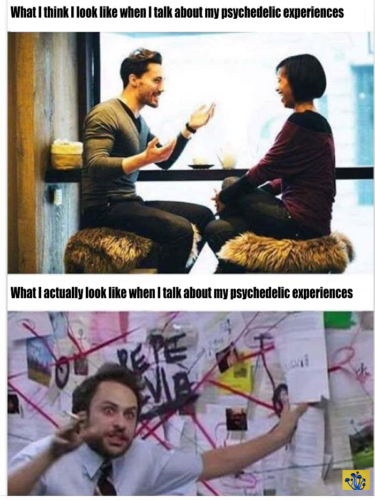

Even though the Internet has led to a sharing of shamanic knowledge completely unprecedented (and impossible) for any other point in the world’s history, it hasn’t filtered down to the mass consciousness yet. Probably it never will – the men of silver and iron and clay cannot be expected to concern themselves with what lies beyond this veil. This essay gives some tips for talking to them about the world beyond without sounding insane.

The most important thing is to have a feel for what the person you are talking to is likely to be able to handle. This means that you have to look for clues from what you already know about them to give hints about what they already believe.

The easiest way to sound crazy is to express a belief that does not accord with consensual reality of the mass consciousness of the people around you. This is true whether you are in meatspace or cyberspace. The lower the intelligence of the person you are speaking to, the less likely it is that they will have challenged any belief widely-held by the people around them.

It is in this will to challenge consensual reality that most people judge sane from insane. All you have to do is to assert that things are not as they are commonly believed to be, and some people will start to consider you crazy. Essentially you only have to contradict the television, or in other cases the radio or FaceBook.

You might start a conversation with a suspected normie by questioning the narrative that you are fed by the network news, or by the broadsheet papers. Even that is enough to sound pretty crazy to most people, who are on the level of “they couldn’t say it if it wasn’t true.” If a person is on this level they are in no way ready to handle the idea that the government has lied to them about psychedelics for the sake of making them easier to control.

A useful tactic here is to point out how the governments and mainstream media of Anglosphere countries colluded to sell the lie that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction in order to manufacture consent for the Iraq War. It’s possible now, though, that a person remembers those times differently and will choose to remember it in a way that denies this collusion.

It pays to be wary of the fact that most people are materialists, which implies that they believe that the brain generates consciousness, and that upon the death of the physical body this consciousness somehow “disappears”. These people consider all kinds of religious ideas like karma and God to be superstitions, and the bitterest contempt is reserved for those religious who believe that the consciousness survives the death of the physical body.

Unfortunately, this belief is also one of the major insights of psychedelics – perhaps it is this psychedelic insight that forms the foundation of most religious beliefs.

Mathematics is the way to get at people who are the hardest to reach. Expressing a sense of awe and wonder at how, for example, the Fibonacci sequence reoccurs in the state of Nature is a good way of getting a person to ask themselves whether there’s something other than sheer chance going on. Other ways are to express similar sentiments about the non-reoccurring nature of pi or the import of Goedel’s Incompleteness Theorem.

The way to talk about it so that it makes sense is by talking about previous beliefs that you once held that you either questioned or abandoned after taking a psychedelic. Usually this makes it possible to apply logic to dismantle one erroneous idea after the other, and it’s seldom necessary to mention that this destruction of illusion was achieved by means of psychedelics (any insight that psychedelics have brought you can be plausibly credited to either meditation or a near death experience as well).

For example, a psychedelicised person might be able to conduct a conversation with a normie about the boundaries of the human body, and how it’s not clear where inside ends and where outside begins. The very idea of selfishness starts to unravel if the idea of what it is that one might be selfish about is challenged, and by such means light can shine through.

This column believes that the ultimate goal of consciousness expansion is apotheosis, where an individual consciousness reunites themselves with the universal consciousness and becomes privy to certain mysteries, such as that there is no such thing as time and that the death of the physical body does not impact the true self.

Contemplation of this alone is liable to induce a psychiatric breakdown in a lot of people. Most people are so utterly terrified of the concept of their future death that they have pushed the very idea of it into a deep, dark part of the mind, only to be ventured into in an emergency. Even fewer people have looked deeply enough into their own minds to have made a surgically precise distinction between consciousness and the content of consciousness.

Starting with such subjects is probably too much. Most people will declare you crazy for talking about them rather than risk psychosis by dwelling on them.

Questioning the materialist dogma that the brain generates consciousness is the quickest way to be seen as crazy. This dogma is taken by many to be the absolute, inviolable and axiomatic truth of reality and conversation along these lines is likely to make materialists fear or despise you.

The best thing is probably to declare skepticism of the claims of a mutual enemy. The Government, the Church or Big Business can all serve as excellent mutual enemies. Skepticism of the claims of these mutual enemies might then be generalised into skepticism about other claims and dogmas.