This reading carries on from here.

In this section (pages 1294-1413), Breivik describes what he predicts will happen when a European civil war kicks off, sometime around 2070 A.D. Chillingly, he is clear about his belief that democracy has already failed. He points out that if Europe is to remain a democracy then it is already lost, because demography has already gone so far as to shift the power into Muslim hands.

After all, if Muslims become a numerical majority anywhere then it is no longer a matter of fighting – they will be able to simply vote any aspect of Islamic culture into law. It is a curious fact of the modern public discourse that few commentators are willing to speak about what will happen if current demographic trends continue, even though the historical example of Lebanon has been clearly described by many, not just Breivik.

A particularly odd paranoid streak, common in European nationalists, comes through in this section when Breivik lists the crimes of the American Empire. This list is not as exhaustive as his list of the crimes of Islam, but it emphasises a point that is not easy for people in the New World to understand: namely, that the idea of “The West” is a New World concept and European nationalists are quite happy thinking of Europe by itself as a self-sufficient system.

Interestingly, here Breivik puts a precise monetary value on his willingness to get rid of Muslims. He states that, when the inevitable deportations begin, every Muslim will be offered 1kg of solid gold to voluntarily go away. $15 billion Euros to get rid of a population of 1 million is a fine exchange in his mind.

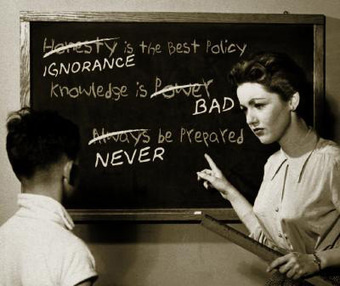

The plans for a cultural conservative revolution here are comprehensive. Breivik writes about the need to reform education so that children are taught that Islam is a hate ideology on par with Nazism. Re-educated is the preferred method for dealing with Marxists, unless of course they are “Category A, B or C traitors”.

Again underlining Breivik’s inability to understand irony, he writes “Crusading is not just a right, but a duty according to Canon Law,” which is precisely the mentality that he is accusing Islam of and which he uses to justify his action. Much like the jihadists he excoriates, Breivik claims that “in the context” of the Islamic invasion of Europe, any action could be considered self-defence, echoing Osama Bin Laden’s justification for the 9/11 bombings.

This section then takes a rather bizarre turn, with a series of cut-and-pastes on religious themes such as the ability of the Christian cross to act as a unifying symbol for all Europeans, how the Lord demands that his followers be warriors, and a fire and brimstone laden spiel about the hell that awaits atheists after death.

Here Breivik mentions explicitly that he considers himself a warrior of Christ and that if he is killed in action he expects to get into the Christian heaven as a martyr.

This section finishes with a c.50 page “interview” with himself, in which Breivik responds to anticipated criticism. Here he again expresses his disdain for Nazism, calling it a “hate ideology” and saying that he could expect the Nazis to turn on conservatives like him as soon as the Marxists were dealt with.

Breivik makes a very compelling argument here. The Marxists claim to oppose Nazism on the grounds that declaring a person to be subhuman and then treating them as such is grossly immoral, yet anyone who doesn’t agree with the Marxist doctrine on every point, no matter how evidently ludicrous and self-defeating, is themselves treated as subhuman. Already the Austrian Government is putting elderly ladies in prison for the utterly preposterous non-crime of “Holocaust denial”.

It’s hard not to appreciate the accuracy of this criticism of the Left’s behaviour.