Our media has been giving us the Two Minute Hate about North Korea for over two decades. Anyone who has read 1984 knows that most of the reason for this is to distract from the crimes of our own politicians and industrial leaders. One of these crimes is the War on Cannabis: Western Governments could learn from the North Koreans how to have a humane, honest and fair cannabis policy.

For the past 40-50 years, Western Governments have conducted a War on Drugs against their own people, without the consent of those people. Trillions have been spent during these decades to persecute tens of millions of Western citizens, many of whom had not caused any harm to anyone. This mass human rights abuse – because that’s what it is – continues to this day, despite small wins for the people in some areas.

This War on Drugs has been justified with a rhetoric so clumsy and corrupt that even a 1930s-era propagandist would be embarrassed by the lack of subtlety. From the infamous “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men” to “Cannabis use causes psychosis” to today’s horseshit stories about how buying cannabis is supporting Mexican narcoterrorism, no more hamfisted effort has ever been made to sell anything.

For roughly half a century, Western families have been ripped apart from having one of their family members sent to prison for a cannabis offence. Tens of millions have been forced into a traumatic encounter with the Police and justice or prison systems, treated as criminals when most were mentally ill and needed help. In America in 2016, there were 574,641 people charged with the crime of simple cannabis possession.

One would expect then, that the punishment for cultivating cannabis in a place as fundamentally evil as North Korea would be horrifically draconian and senseless. If it’s up to seven years imprisonment in New Zealand it must surely be life in prison or even execution there.

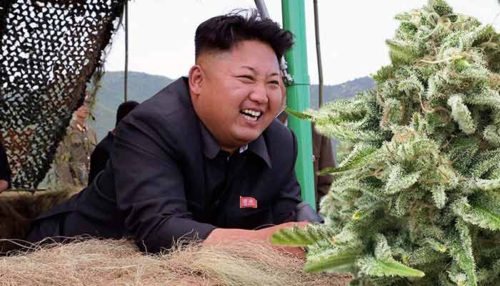

To the contrary – far from scheduling cannabis as belonging to the most dangerous category of addictive drugs with no medicinal value as America does, North Korea doesn’t even consider cannabis a drug. Not only are people free to cultivate it without sanction, but it grows freely by the roadside in many places, being a weed and not being subject to eradication programs. North Koreans are free to harvest and smoke it every single day – and they do.

Many would personally be happy to trade all the supposed Western freedoms to drink booze, watch television and chase loose women for the freedom to smoke cannabis, have quality conversations with intelligent people and at the end of the night still be capable of maintaining an erection. So one has to ask: who’s actually better off?

The thawing of relations between the West and North Korea might have implications for cannabis policy in the West. Those Westerners who are still labouring under primitive superstitions such as “cannabis causes brain damage and therefore people should go to prison for it” might learn something from the more enlightened approach taken by the North Korean Government.

Perhaps North Korea could send advisors to the West to educate our politicians about how large industries conspired to make cannabis illegal for the sake of wiping out a competitor, and that keeping it prohibited is actually an immoral thing to do. These North Koreans could also be tasked with going through our Police and justice system employees to root out the sadists who believed that imprisoning someone was ever a fair or reasonable response to drug possession, because they are morally defective and cannot be trusted to serve the public.

*

If you enjoyed reading this essay, you can get a compilation of the Best VJMP Essays and Articles of 2017 from Amazon for Kindle or Amazon for CreateSpace (for international readers), or TradeMe (for Kiwis).