There is a lot of discussion about power dynamics, and whether the people who end up at the top of them have got there through competence or by machination. A person’s position on this question will correlate extremely strongly with their level of revolutionary zeal. This essay seeks to illuminate the subject from an esoteric perspective.

There are three ways for a person to dominate another one. They can do so physically, in a manner akin to the effect iron has on clay; they can do so with trickery, in a manner akin to the effect silver has on clay; they can do so by offering up an example of behaviour that ought to be emulated and allow the clay to imitate it, in a manner akin to the effect gold has on clay.

For the most part, people can generally agree that hierarchies of iron are illegitimate, except for the odd occasion when they are entered into legitimately, such as an army volunteer or a consensual BDSM participant. In nature, the effect of iron upon the clay is necessarily coercive and non-consensual, and the majority of people find this sort of thing unpleasant, so hierarchies of iron are generally discouraged.

Everyone generally agrees that hierarchies of gold are ideal. The ideal form of hierarchy is for an excellent person to behave excellently and for people who aspire to a similar excellence to support that first person on account of their great deeds. This is identical to the philosopher-king model proposed by Plato in The Republic and most people can immediately see the merits in it.

The difficulty arises when a hierarchy of silver is formed in imitation of the hierarchy of gold. To some extent this is unavoidable because almost all hierarchies of silver are – in the human world at least – imitations of the hierarchy of gold.

For example, a man might arise who is crafty enough to swindle the people around him into believing whatever he said. He might then, as many men have previously chosen to do, take advantage of this opportunity and tell them all that he’s a living god and that his every word is infallible and that his will cannot be questioned.

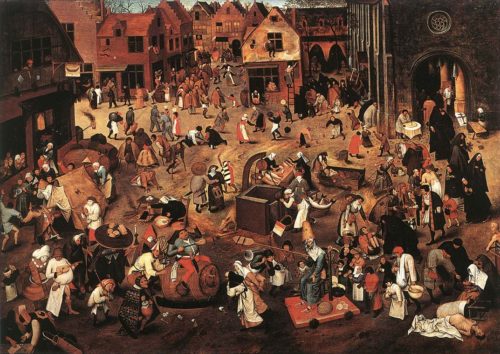

This is an ancient trick – it worked 10,000 years ago and the Pope is still running it now. It works because the hierarchy of silver built by the swindler is sufficiently close to the ideal hierarchy (assuming a sufficient level of stupidity among the peasantry) that the dull cannot tell the difference, and those who do can be silenced by swift application of sharp iron.

Hierarchies of silver have a multitude of forms, as numerous as there are opportunities to cheat others. They all have in common, however, the property of illegitimately acquiring and concentrating power.

Either they put the power into the wrong hands or they put it in the right hands but in the wrong amounts. The hierarchies of silver share this quality with the hierarchies of iron, but unlike the iron they do not do so by acquiring powerful weapons, but rather by controlling the minds of the men who control the weapons.

In other words, a hierarchy of silver will misdirect the men of iron. This means that the men of silver will make laws that are unjust, such as levying unfair taxes, or banning certain luxuries that should remain freely available. The men of silver will not be able to adjust their system to reflect accurate criticism because, not being of gold, their hierarchy is not intended to represent correct rule.

Hierarchies of gold are when the right people have the power in the right amounts, and usually result in Golden Ages for the people within them. However, they are more fragile than the others, in the same way that gold is the softest of all metals. The proximate challenge for the philosopher-king is usually keeping the men of silver from hatching some plot to steal the loyalty of the men of iron.